Whilst the sustainable development agenda may offer a unifying lens through which we focus our efforts to build sustainable cities and societies, it sits within a narrative of economic growth that demands development regardless of the costs. The regeneration of Sewoon Sangga in Seoul challenges this predicament, perhaps hinting towards an architecture that transforms rather than consumes – an architecture of degrowth.

We attach value to many characteristics of our cities, whether that be mobility, access to infrastructure, openness or the presence of nature. But regardless of how important these attributes may be, the prevailing force that defines their existence, as well as their quantity and quality, is the pursuit of economic growth. Without growth our advanced capitalist economies cease to function, and this demand has pervaded our thinking about how cities work and the policies that shape them. Success is represented by the percentage figures that describe the health of our economies, ensuring that we strive not just for growth, but growth for the sake of growth.

Architecture has become a primary measure of this growth – a visual and tangible representation of a ‘healthy’ economy – from mass speculative housing to the construction of iconic forms that symbolize upturns in economic fortunes. Whilst the 2008 financial crash provided stark evidence of the risks associated with regarding building stock as financial instruments, strategies of urbanism remain transfixed on continuous construction (and demolition, as the other side of the city development coin). The world construction industry now accounts for some 14% of global GDP, ensuring that policies prioritize construction over considered development. Growth for the sake of growth demands development for the sake of development.

If the state of our economies is reflected in the rise and fall of urban forms, so too is the condition of our societies and the rate at which we are approaching, or exceeding, environmental limits. The dogma of perpetual growth has infiltrated not just the way we shape our cities, but also the values we project upon our buildings and how we interact within them. Regardless of how virtuous our aims might be, as architects our task is usually more – to build and to produce, as we consume.

So how do we begin to improve our cities outside of the narrative of growth? Can architecture be an instrument for positive transformation without demolishing to construct? What role do architects play in conditions that increasingly appeal for us to produce (and consume) less?

The concept of sustainable development has emerged as the universal consensus on how to improve quality of life whilst reducing our environmental impact, with the United Nation’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals setting ambitious targets on how to alleviate poverty, increase social equity and restrict climate change by 2030. Goal 11 represents the targets for sustainable cities and communities, coming in just after Goal 8 – the ambition for decent work and economic growth. And here lies the predicament; the agenda for sustainable development may aim to address environmental issues and improve quality of life, but it does so within the parameters of continued economic growth. If we accept that the ‘cult of growth’ has been responsible for the exponential rise in processes of extraction, production, consumption and development, which in turn has led to the global environmental (and societal) crisis, then perhaps we should question the aims of development if its agenda is economic growth.

Whilst the sustainable development agenda provides an invaluable lens through which to focus our collective architectural efforts, the concept of degrowth offers a useful counterpoint, challenging the aims of sustainable development if it only exists on an economic trajectory. Emerging from both a Marxist intellectual territory in France (from the likes of Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen and Jean Baudrillard) and a grassroots movement in various Northern European countries (co-housing was pioneered in Denmark in the 1970s) , degrowth advocates the improvement of quality of life and social wellbeing without an increase in consumption. Degrowth thinkers and activists support the reduction of production and consumption – the contraction of economies – arguing that overconsumption lies at the root of long term environmental issues and social inequalities.

So if perpetual growth has been the generating principle of 21st century cities, degrowth demands we turn our attention to methods of reduction and consolidation (Keller Easterling suggests that architects are well equipped to master methods of subtraction, beyond endless addition). Perhaps this seems self-evident but it poses something of a challenge to architects, reliant as we are on opportunities to construct – to develop and consume. Are there opportunities for an architecture that exists outside of the growth agenda, enhancing societies whilst rejecting the demands of economic growth? And what might this – an architecture of degrowth – look like?

There are many aspects of contemporary cities that represent improvements of quality of life without greater consumption – mobility infrastructure, models of shared living and diversified building uses all have benefits for social dynamics whilst causing some kind of economic shrinkage (less consumption of fuel, materials and ‘goods’) – but these projects are not often celebrated as architecturally aspirational, nor featured on architectural websites such as this. Architectural value is still overwhelmingly dictated by novelty, and therefore growth.

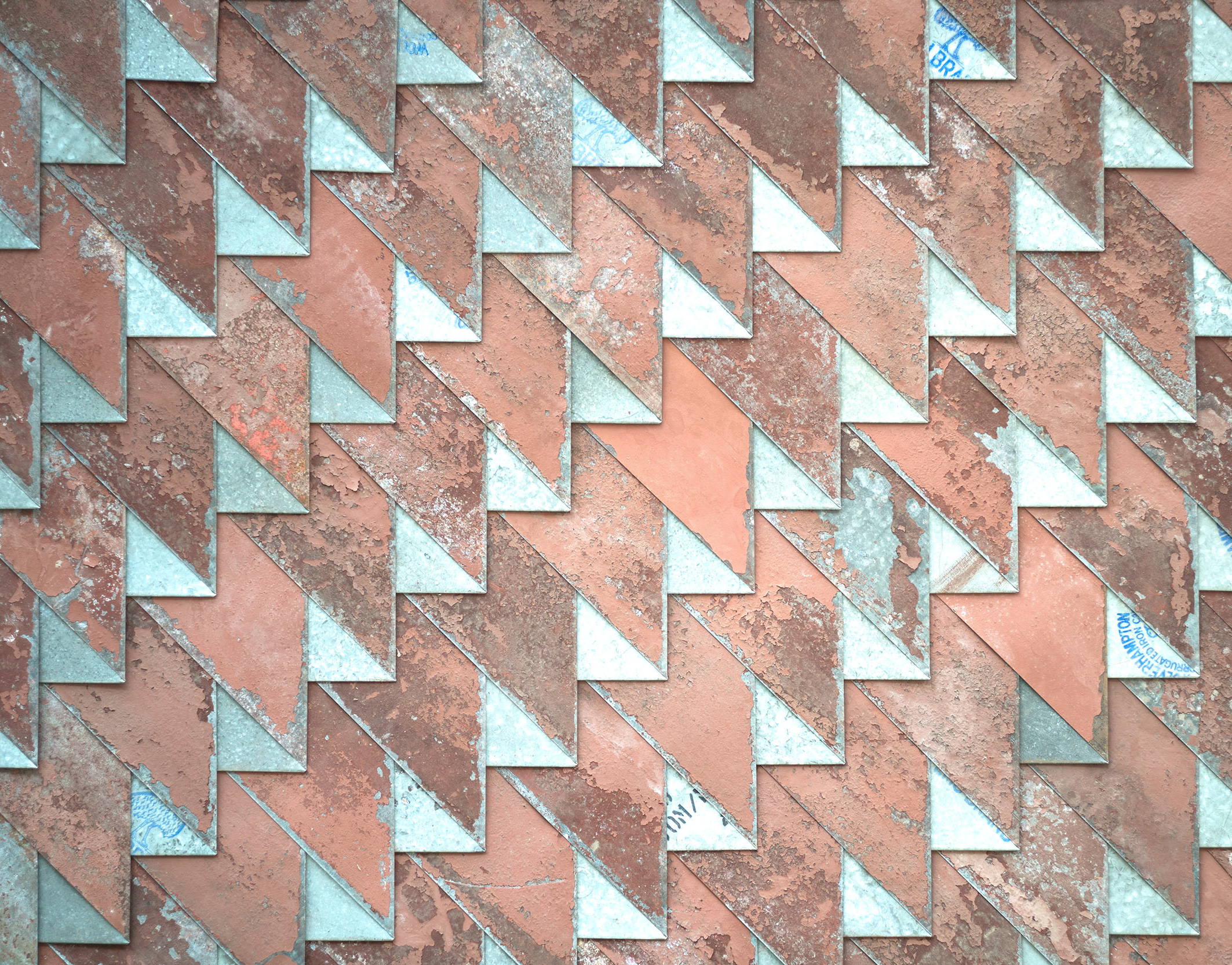

The regeneration of Sewoon Sangga, a kilometer long concrete megastructure in Seoul, South Korea, might just represent an architecture of degrowth, unique as it is in its scale, vision and political context. Designed in the 1960s by South Korea’s foremost modernist architect, Kim Swoo-geun, the monolith emerged from the country’s rapid economic and urban growth following the Korean War; a representation of Korean modernity that seemed brave and excessive even within the context of the rapidly expanding city of Seoul. Its labyrinth of staircases, alleyways and elevated walkways connect a microcosm of functions, combining shops, offices, restaurants and residential units above a vibrant base of manufacturing activities.

Yet it wasn’t long before the structure’s vision was corrupted, and by the late 1970s the structure was rife with illicit activities and illegal trading, leading to calls for demolition from successive mayors. The building’s social problems were attributed to the failures of its architecture and, like many postwar brutalist structures, it was viewed as an opportunity to clear the way for high-rise speculative housing, destined to become another spectacle of destruction for the sake of future growth.

Yet Sewoon Sangga hasn’t been demolished, and is instead undergoing a subtle but inspired regeneration initiated by Seoul Metropolitan Government and the city’s mayor, Park Won-soon. The project is interesting not only in that it has rejected the demands of economic growth through development, but is also taking steps to avoid the risks of gentrification, such as ensuring the right to remain for many of its inhabitants and prioritizing connectivity and diversity over visual appearance (you wouldn’t necessarily notice any changes at first glance). The project’s phased regeneration is being supervised by the influential City Architects department (60 architects led by Kim Young-Joon) that has been responsible for an array of citizen-focused projects including the Seoullo Skygarden.

Rather than relying on the sale of divided units and an injection of consumption activities, the project has focused on subtle interventions that connect the building’s multitude of programs with each other and the surrounding city, such as a sloping square that connects the elevated walkways with the street. Skilled craftsmen that have occupied the building for decades now work amongst fab-labs and artists studios, and the rigid superstructure is not just being used, but moulded and transformed to suit the myriad of users and functions that inhabit it. The significant involvement of the City Architects department is demonstrating that when architects take positions of influence, they can be empowered to dictate urban strategies that value more than just growth, short-circuiting the usual client-architect demand dynamics.

Whilst not all cities have a superstructure in need of regeneration, the ongoing transformation of Sewoon Sangga hints towards the opportunities made available when resolute architects question the dogma of growth development and find ways to enhance society with minimal intervention. As we continue to demolish (often relatively young) buildings in favor of speculative housing or commercial operations, Sewoon Sangga represents a refreshing and subtly radical shift in priority – from economic growth to social well being. At its most extreme, degrowth might demand that we refuse to build (which in many cases might be the answer). But Sewoon Sangga’s regeneration hints towards the transformative potential of modest but thoughtful design projects, suggesting a form of sustainable development that can flourish beyond the demands of economic growth.

Originally published on arcspace.com

Further reading:

Charles Eisenstein – Sacred Economies : ‘What does economic growth actually mean? It means more consumption.’

n’UNDO : ‘proposing and demonstrating that it is possible to build more and better from reduction, contention and reasoned decline.’

Keller Easterling – Subtraction : ‘Architects trained to make the building machine lurch forward may know something about how to put it into reverse.’