This text is one of a five part series exploring the themes of the Danish contribution to the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Commissioned by Natalie Mossin (curator of the Danish Pavilion) and the Danish Architecture Center / arcspace.com

Tasked with refurbishing 1001 homes in a Copenhagen suburb, Vandkunsten architects saw an opportunity to revolutionize renovation practices through material circularity and democratic design. Their exhibit at the Danish pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale presents innovative strategies for repurposing materials, but also speaks of the compromise intrinsic to collaboration.

The homes of the future are already built. New housing construction has long been an engine for growth in Northern European cities, but flatlining populations and steady economies have begun to reduce the demand for new homes. Denmark continues to build around 20,000 new homes each year, but this accounts for just 1% of the total housing stock. As in many European countries, the vast majority (94.6% in 2025) of Denmark’s required housing is already built, owned and lived in.

Copenhagen continues to build in an impulsive attempt to curtail the rising cost of homes and ease the resulting affordability crisis, but it is becoming increasingly clear that this will only ever be a fragment of the solution. If cities have already reached an appropriate point of saturation, then strategies of repair, maintenance, adaptation, renovation and restructuring will become ever more important aspects of the construction industry, and thus of architectural practice. This encompasses the need for routine upkeep of aging buildings, but also the more urgent requirement to drastically improve energy efficiency (Europe’s building stock currently accounts for around 40% of total energy consumption) and resource preservation. Demographic shifts and changing family structures are demanding new types of homes, but perhaps these changes can also be accommodated through adaptation and repurposing.

So if the industry has no choice but to engage more directly with the built environment as it exists, why is it that housing policies and environmental regulations are so focused on new construction, neglecting the existing housing stock? This is reflected in the architectural profession’s enduring inclination toward innovative, new-build housing projects, and together these conditions limit the opportunities for innovation in the field where they’re really needed - renovation.

This debate comes to the fore in the story of Albertslund South, a vast 1960s housing development in the suburbs of Copenhagen. Designed by social housing pioneers Fællestegnestuen, Albertslund is one of Denmark’s largest housing developments, providing affordable housing for 5,500 tenants. The project was experimental and innovative in its applied construction techniques, its ‘atrium’ housing design, and the urban plan that organizes the district - rows of introverted brick bungalows amongst a labyrinthine network of streets and paths. Albertslund’s uniformity is compelling as a direct representation of the democratic Danish welfare system; equity in housing and therefore in opportunity. Despite sitting firmly in the peripheries of Copenhagen’s urban development, Albertslund has developed a strong and committed community.

But fifty years of use has made its mark on Albertslund’s poor construction quality, and in 2012 the municipality launched a competition in search of a strategy for the complete renovation and revitalization of the area. The Danish architecture office Vandkunsten won the competition with a simple proposal; ‘change to preserve’, by closing the material loop. This was developed through an understanding of the collectively produced cultural value and sense of pride embedded in a place as unique and equitable as Albertslund, but also an acceptance that these qualities could not be preserved without extensive renovation works.

In calculating the figures associated with a project of this scale, Vandkunsten were struck by the sheer volume of construction waste that would result from a typical renovation process - the flooring alone amounted to 80,000m² of solid beech parquet that would usually be destined for incineration (to provide district heating). Vandkunsten’s plan therefore aimed for material circularity, where dismantled components could be repurposed and used anew. Timber flooring could become a porch. Patinated roof tiles could become a wall cladding. An inventory of options were drawn up and preliminary assessments were carried out to evaluate the environmental and economic impact of different strategies, taking into consideration parameters such as LCA (Life Cycle Analysis), LCC (Life Cycle Costing), and energy needs, as well as cultural and social values. Vandkunsten saw the dismantled materials as embodying three kinds of value; a resource value and an economic value, but also a cultural value that was closely connected to the site and its history.

Six prototype homes were renovated alongside an extensive catalogue of online options, from which tenants could select the components that would comprise their refurbished home and see the implications for their rent. Danish social housing tenants are formally entitled to direct these renovation decisions, and elected tenant organizations play a central role in any kind of development (meetings of 800 tenants took place in a local theatre). This strong collaboration between tenants, municipalities, and architects, as well as housing organizations and suppliers, creates the conditions for a determinedly democratic design process, and Vandkunsten hoped that this ‘social strategy would create stronger ownership between the tenants and the development’.

Their vision was 1001 different renovations, each showcasing innovative ways of repurposing materials and proclaiming the individuality of its occupant.

But the reality will be 1001 very similar renovations, as most tenants simply chose the same set of components. While the interiors may reveal different layouts, fixtures and decorations, the majority of Albertslund’s residents deemed the reuse strategies too avant-garde and opted for the external components that matched their neighbors, retaining the architectural homogeneity and simplicity that characterizes the area. Democracy in action.

‘We failed completely in our attempts to implement reuse strategies in the actual renovation.’ Søren Nielsen, Partner at Vandkunsten

Undeterred by the dismissal of their reuse proposals, Vandkunsten collaborated with demolition contractors and used-material suppliers to find other ways of putting dismantled components to use. They may not be recirculated within the project itself, but many are now available on the European market through online materials suppliers such as Genbyg A/S. Vandkunsten’s then committed themselves to the optimization of the building process itself, reducing the time that each renovation would take (from 108 days to 68) and implementing other strategies such as ‘design for disassembly’ (the second phase of the project is due to be completed in 2022).

More significantly, Vandkunsten refused to let go of their repurposing concept and initiated a major innovation project, Rebeauty - Nordic Built Component Reuse, to record and promulgate their findings in collaboration with Genbyg, Asplan Viak, and Malmö Tekniska Högskola. The team systematically produce and analyze 1:1 prototypes using all kinds of reclaimed building materials, repurposing them with a commitment to their 'aesthetic qualities as well as their performance’.

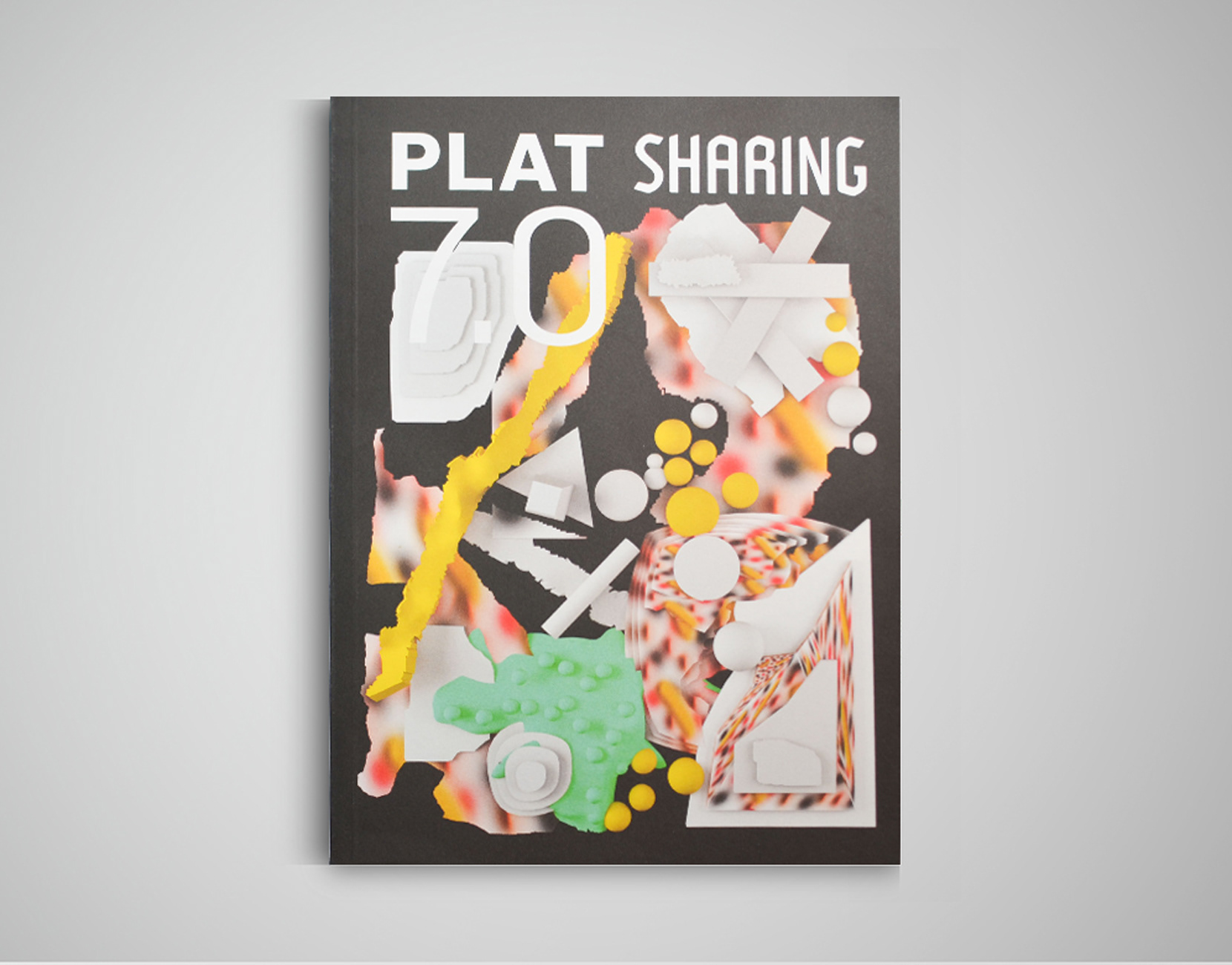

It is some of these prototypes that constitute Vandkunsten’s contribution to the Danish pavilion at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale. Reclaimed timber flooring makes up a partition wall, a metal facade is formed from flattened ventilations ducts, and an exterior cladding is made with patinated roof tiles. These installations intend to show how energy, money and resources might be conserved, but also the aesthetic value in doing so. This is fundamental to Vandkunsten’s approach - only when repurposed components become culturally accepted and appreciated will material circularity have a chance of taking hold. In this way Nielsen imagines the Venice Biennale exhibit as a ‘possible Albertslund project in perhaps 20 or 30 years when we have been culturally acclimatized to reuse materials’. (Outdated regulations are holding this process back, with insufficient standards to prove reused materials are safe and clean for use).

Albertslund reminds us that democratic and collaborative design processes come with an intrinsic level of compromise, but this doesn’t have to be to their detriment. Vandkunsten’s vision of large-scale reuse and material circularity may have been molded into an exercise in construction optimization and tenant autonomy, but they have used these compromises as the catalyst for a research project that has produced genuinely innovative and scalable ideas, with the potential to impact far beyond the limits of Albertslund. As development in circular economies and material reuse gains traction, projects like this will be ever-more central to the demolish, build, or renovate debate.

Danish pavilion photographs © Rasmus Hjortshoj - COAST

Albertslund South photographs © Torben Eskerod

This text is the third in a five part series exploring the themes of the Danish contribution to the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Commissioned by Natalie Mossin - curator of the Danish Pavilion, and the Danish Architecture Center.

View at source - published on arcspace.com