Published in Arkitekten 02 Kultur - March 2023

Published in English by Folly - Book Four

A glance at most architectural magazines or awards shortlists will offer you a wealth of new build projects - documenting and celebrating the novel and the new. Iconic and singular buildings, built from scratch and ignorant to what they might be replacing, often sit at the top of this pile. These are usually attributed to a singular author, and the date at which they were completed is defined and recorded. These singular acts of authorship fit neatly within the recognised canon of architectural progress, and can be read as belonging to a certain style or movement.

But as the climate crisis deepens, and our profession becomes ever more aware of its role in designing buildings and structures that contribute to this crisis, the case for such new build projects is becoming increasingly difficult to justify. New buildings may be more energy efficient than existing ones, but the majority of buildings needed by 2050 are already built (in the UK this figure is at least 80%, according to the UK Green Building Council). Even more difficult to justify is the act of demolishing this existing built fabric in order to make way for a new building - with the ensuing wastage and its inherent carbon cost. Regardless of how highly performing that new building may be in operation, it will likely take decades to outweigh the upfront carbon cost that would be saved by retention rather than demolition. As Carl Elefante reminds us, ‘the most sustainable building is the one that is already built’.

This realisation puts a sharp focus on retrofit - the act of repairing and upgrading existing buildings to improve their energy efficiency, making them easier to heat and power, and better at retaining that heat whilst utilising lower consumption systems and technologies. In the majority of cases, the embodied carbon of a building retrofit will be significantly lower than a wholly new structure, especially after taking any negated demolition into account. Repair can be targeted to improve the longevity of an existing building’s embodied carbon, and this can in turn reduce the demand for new buildings to be built.

The conversation is particularly relevant in the UK, plagued as it is with one of the oldest and leakiest housing stocks in Europe. But while the need to decarbonise these homes, as well as existing buildings in general, is so evident, the UK is far behind the EU in its annual rates of renovation, as well as in reducing its primary energy consumption. The problem is complicated by the fact that retrofit and new build are deemed as wholly different exercises, with separate standards, targets and funding streams. In everything from thermal performance requirements to funding allocation, there is less aspiration in the retrofit sector than in the new build sector, meaning the environmental performance and quality of these projects is often lacking. Government policies aimed at improving energy efficiency are consistently undermined, and the oft-promised ‘national effort’ in installing insulation and heat pumps has never materialised at a meaningful rate. There are of course fundamental differences between building from scratch and working with existing fabric, but surely they should both be approached with the same ambition, care and diligence.

But as the climate crisis deepens, and our profession becomes ever more aware of its role in designing buildings and structures that contribute to this crisis, the case for such new build projects is becoming increasingly difficult to justify. New buildings may be more energy efficient than existing ones, but the majority of buildings needed by 2050 are already built (in the UK this figure is at least 80%, according to the UK Green Building Council). Even more difficult to justify is the act of demolishing this existing built fabric in order to make way for a new building - with the ensuing wastage and its inherent carbon cost. Regardless of how highly performing that new building may be in operation, it will likely take decades to outweigh the upfront carbon cost that would be saved by retention rather than demolition. As Carl Elefante reminds us, ‘the most sustainable building is the one that is already built’.

This realisation puts a sharp focus on retrofit - the act of repairing and upgrading existing buildings to improve their energy efficiency, making them easier to heat and power, and better at retaining that heat whilst utilising lower consumption systems and technologies. In the majority of cases, the embodied carbon of a building retrofit will be significantly lower than a wholly new structure, especially after taking any negated demolition into account. Repair can be targeted to improve the longevity of an existing building’s embodied carbon, and this can in turn reduce the demand for new buildings to be built.

The conversation is particularly relevant in the UK, plagued as it is with one of the oldest and leakiest housing stocks in Europe. But while the need to decarbonise these homes, as well as existing buildings in general, is so evident, the UK is far behind the EU in its annual rates of renovation, as well as in reducing its primary energy consumption. The problem is complicated by the fact that retrofit and new build are deemed as wholly different exercises, with separate standards, targets and funding streams. In everything from thermal performance requirements to funding allocation, there is less aspiration in the retrofit sector than in the new build sector, meaning the environmental performance and quality of these projects is often lacking. Government policies aimed at improving energy efficiency are consistently undermined, and the oft-promised ‘national effort’ in installing insulation and heat pumps has never materialised at a meaningful rate. There are of course fundamental differences between building from scratch and working with existing fabric, but surely they should both be approached with the same ambition, care and diligence.

Another practical consideration in the UK is the role of VAT (Value-Added Tax), which is currently zero-rated for new build homes, while it is at the standard rate of 20% for retrofit projects. This shifts the financial equation in favour of demolishing to rebuild, over renovating existing stock. The UK government has recently cut the tax rate on retrofit materials (insulation, solar panels and heat pumps, amongst other things) to 0%, which helps to redress this imbalance, but it is an approach that needs to be expanded. There have even been calls to reverse the VAT strategy altogether - putting higher tax rates on new build projects and cutting tax on all retrofit, repair and alteration projects. This would go some way in shifting the economic equation in favour of retrofit over new build - a necessary step in persuading developers, clients and the general public that repair and renewal is a viable option.

While the practical separations between retrofit and new build may, with time, soften, the architectural profession has also long been complicit in retrofit’s secondary status.

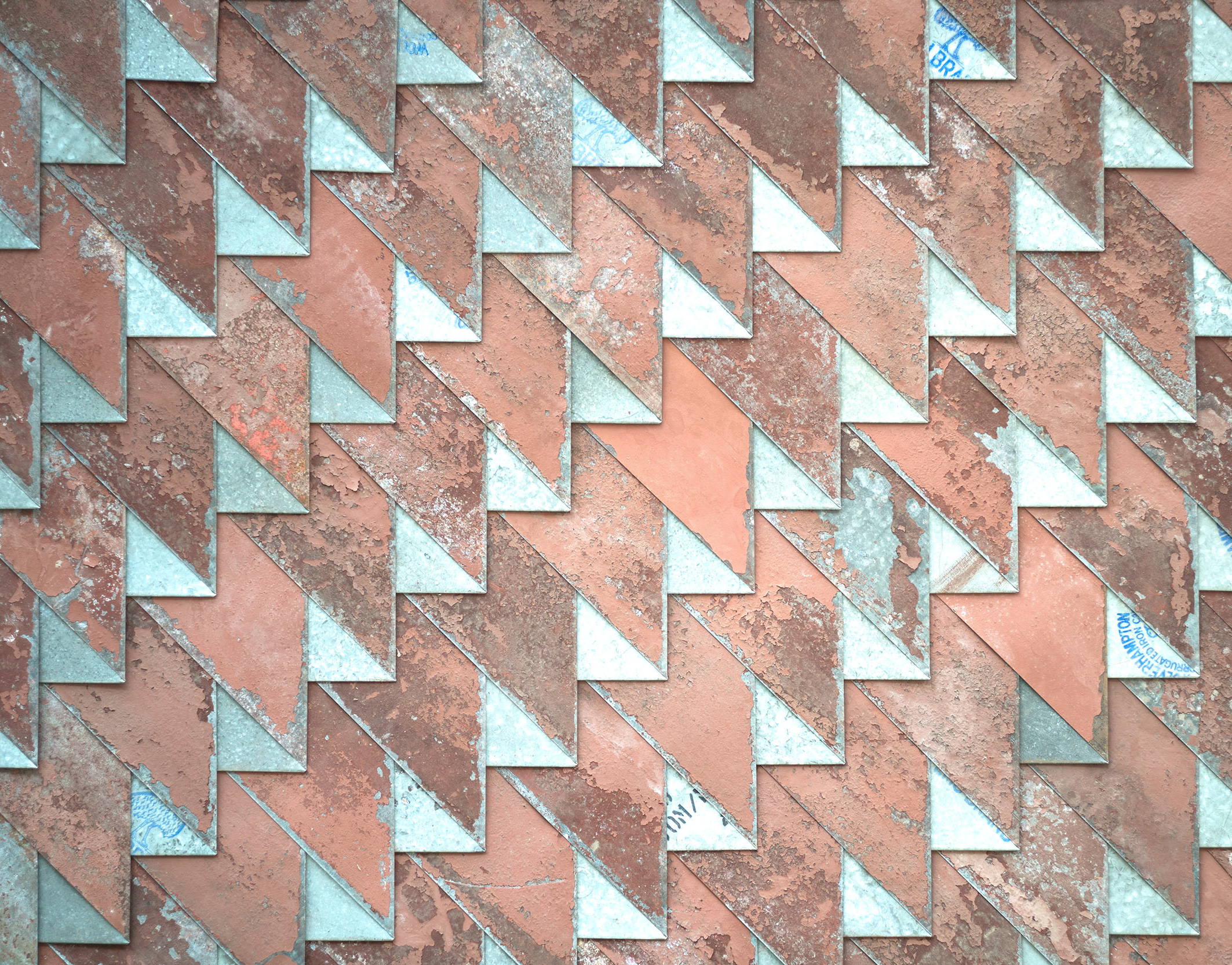

While retrofit and renovation has always had a place in the practice of architecture, it is usually in the shadow of the new build, and thus given less veneration or attention. The very idea of retrofit fundamentally challenges architecture’s obsession with the idea of the single author. It requires an expansion of the definition of architecture to include buildings that have evolved and transformed over time, and made by many hands and many ideas. These projects become perpetual processes of repair and renewal, and can’t be fixed in time or clearly attributed to a singular author. They become acts of communal building and alteration. This speaks to an understanding of buildings as palimpsests, with ever-growing complexities and irregularities that are not traditionally recognised within the architectural canon.

The architect Níall McLaughlin, in his keynote lecture at the Architect Journal’s inaugural Retrofit First conference in London, argued that this shift in thinking is fundamental if we are to respond clearly and effectively to the climate crisis. This is particularly notable coming from McLaughlin, who is recognised for his singular, new build projects, and was recently awarded this year’s RIBA Stirling Prize, the UK’s highest architectural award, for his entirely new build Magdalene College library project. Looking back at past winners, there have only been a handful of retrofit projects - evidence that the profession is still upholds the idea that new build, singular acts of authorship, are the pinnacle of architectural culture.

Shifting our profession’s focus to retrofit demands we reconsider everything from how we educate new architects, to how we commission projects, the standards and rules we apply to them, and the buildings we celebrate with awards and press coverage. There is a clear academic justification for this in the assumption that a building retrofit has lower embodied carbon than a new structure, but this necessity should be accompanied and reinforced by a more total reframing of what architecture is.