It is claimed that the green glass references the 'verdigris on Copenhagen’s characteristic copper spires', or the water, or the sky. Photograph © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST

DAC Passage leads beneath the water line, connecting with the city via DAC’s entrance. Photograph © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST

BLOX encapsulates the road, isolating it structurally to reduce the sound of traffic. Photograph © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST

DAC’s exhibition stair provides direct views in the fitness center. Photograph © Hans Werlemann, courtesy of OMA

DAC’s main exhibition hall is overlooked by the many surrounding functions. Photograph © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST

Following a public outcry, uninterrupted access to the harbor edge has been retained. Photograph © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST

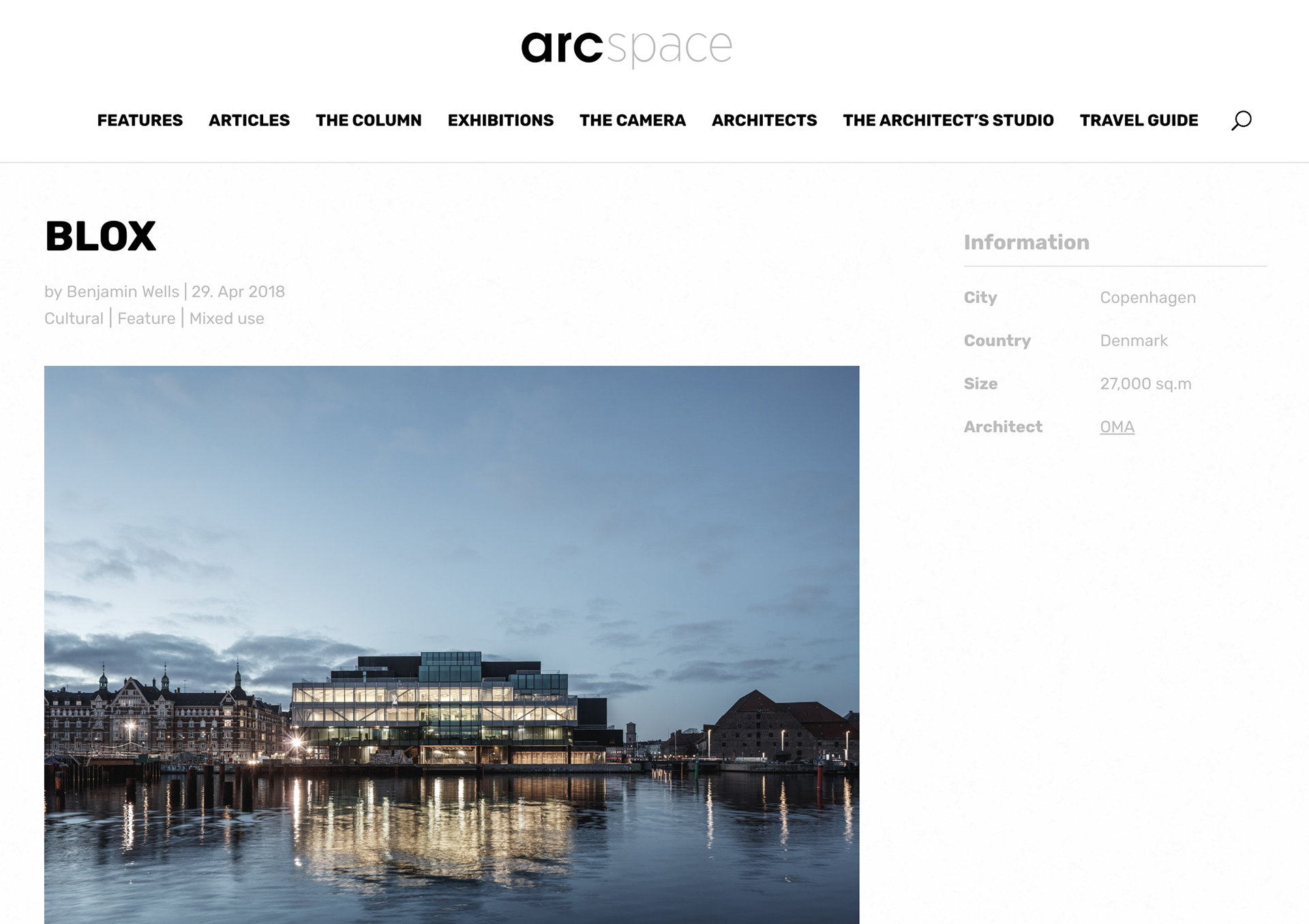

BLOX replaces a royal brewhouse that once stood on the site. Photograph © Rasmus Hjortshøj – COAST