Published in Baumeister April 2024

On the Southeastern edge of Brussels, where the city meets the vast Sonian Forest, a hulking figure of cor-ten steel and golden glass rises from a rolling landscape of lakes and Beech trees. Standing like a gatehouse defending the city, La Royale Belge was designed as the corporate headquarters of the insurance company of the same name, and was intended to be a physical representation of the power and innovation of the company. It was designed in 1965 by French architect Pierre Dufau and Belgian architect René Stapels, who went on to design several important buildings in central Brussels that employ details developed for La Royale Belge. Completed in 1970, its construction was a monumental endeavour; the existing lake was reformed, a waterway was diverted, and 230,000m3 of earth was moved. The construction was incredibly carbon intensive, with vast sums of concrete and steel required to assemble a building at this scale and ambition; 39,000m2 of office space for up to 2,500 employees, on a 10 hectare site.

The building can be read as two primary parts; a cor-ten steel cruciform tower, and an insitu concrete podium, of three storeys above ground and another two below. A second concrete block intersects the main podium at a complex junction of levels and structure, across which sits a technical shaft that spans over five storeys. La Royale Belge takes many cues from Eero Saarinen’s 1963 John Deere & Company headquarters in Illinois, which the architects had visited in 1965. Saarinen's building was the first in the world to use a cor-ten steel structure, and La Royale Belge was one of the first in Europe, and the first in Belgium, to employ the same structural material.

The external structure of the nine-storey tower gives it a complex, layered composition that animates the gold-tinted glazing for which the building is known. The edges of the top two floors are stepped back, exposing the fact that these slabs are suspended from the vast steel beams overhead; column-free suites with framed balconies for the executive floors. The podium reads more like a Miesian pavilion, with a glazed curtain walling spanning both floors, concealing rather than expressing the structure that holds it. This contains a vast, opulent, marble-clad entrance hall, leading to two wings of split-level office space, and a restaurant atop underground parking in the lower intersecting volume. The tower and the podium are united by the third floor, with its broad concrete columns holding the tower aloft, and the marble-clad lift lobby that rises through the entire building as its primary circulation and centre of gravity. This ensemble of parts became a significant icon in Brussels from the moment it was inaugurated, realising a corporate modernist dream of the singular edifice, innovative in its assembly and material-use, commanding the natural landscape it sits within.

Yet as working practices and corporate ideals shifted over the preceding fifty years, the building struggled to adapt, and in 2017 AXA (with whom Royale Belge had merged) decided to move its operations to central Brussels, and the building was left dormant. It was quickly placed on the city's heritage list, ensuring it could not be demolished. The building was eventually bought by a consortium of Belgian investors, who launched a competition through the Brussels Bouwmeester program in 2019. A joint entry between London-based Caruso St John and Antwerp-based Bovenbouw was selected as the winner, and following a highly collaborative process with executive architect DDS+, heritage specialists, city representatives, many consultants and various interior designers at later stages, the building's renovation was completed in 2023.

Due to the building's heritage status, alterations to the external appearance are almost imperceptible, despite being extensive. The cor-ten structure was tested and deemed to have an acceptable remaining lifespan, but the glazing was replaced throughout, in order to bring it up to contemporary thermal and solar standards, while matching its original appearance as closely as possible. Extensive prototyping was carried out to ensure that the glazing retained its golden hues when viewed from outside, while maintaining maximum transparency from within. High performance insulation was integrated into junction details, so that the facade has expanded outwards by just 5cm. The most significant changes to the external expression of the building are a series of new openings cut into the concrete walls of the first floor podium, bringing daylight and access to previously unused spaces, and a large terrace built over the West-facing pond, connected to the new food hall.

Internally, the alterations to the building are many, but interspersed - a series of targeted interventions, primarily focused on removing decades of accumulated services, building systems, and decorative layers, in order to reveal the building's original assembly and intention. In the entrance foyer, sections of the bordering marble-clad walls have been opened up to the split-level office spaces behind, while a reception bridge spans a void where escalators once brought visitors up from the basement levels, bringing a new focal point to the space as well as a place to gather. A new hallway is carved out between the foyer and the food hall, and here the coffered slabs and services are exposed, pools of light illuminate the floor from repurposed pendants, and scalloped panels line the walls in a dark felt - establishing a robust and light-touch architectural language that is traced through the building's new spaces, and sits in contrast to the refined opulence of the entrance foyer and lift cores.

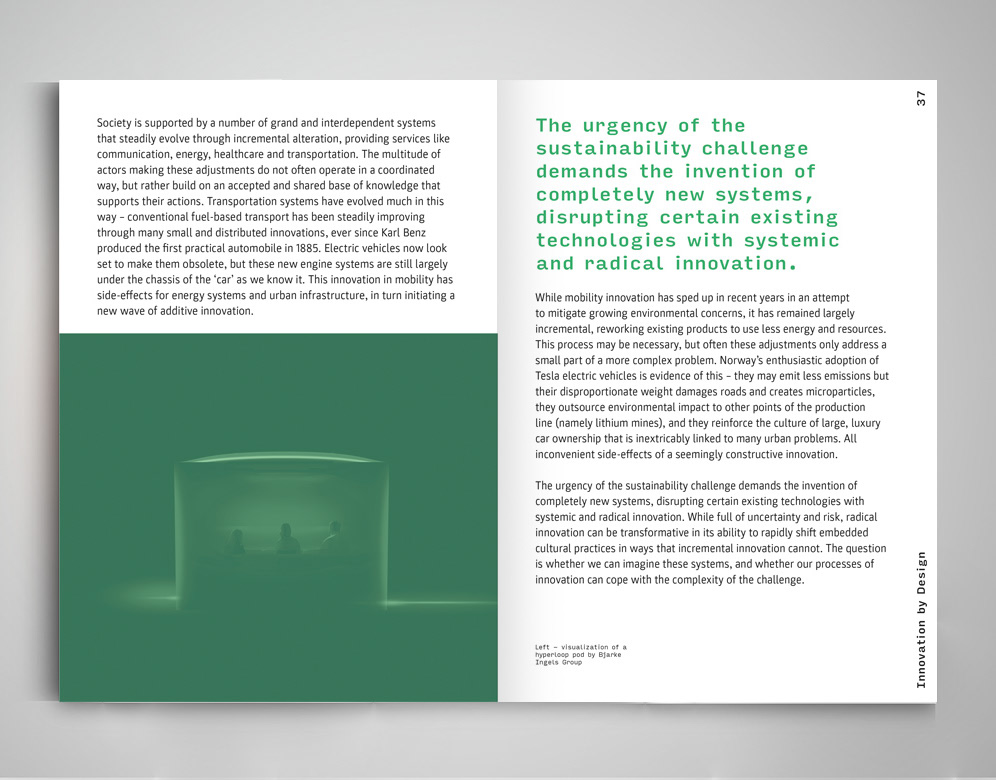

This hall leads to the project’s main intervention, a 21m-wide circular atrium that is cut through three floors of the podium, straddling the complex junction of levels and structure mentioned above. Sweeping staircases, topped in terrazzo and traced with a dark Oak handrail, connect a host of new functions; the food hall, several office spaces, meeting and conference spaces, a sports and wellness centre, and the lobby of a hotel that occupies the lower three floors of the tower. Reminiscent of a Gordon Matta-Clark ‘anarchitecture’ project, the atrium is an exercise in subtraction, in order to bring connection, circulation and daylight into previously unused areas of the building, and at a scale ambitious enough to hold up against the sometimes overbearing architecture of La Royale Belge.

Four new columns, echoing the original in their design, support the vast diagrid concrete roof overhead. Between them is a large new rooflight occupying the void of the former technical shaft, with suspended stainless steel triangles completing the pattern of the diagrid while reflecting daylight deep into the plan. This is characteristic of the project's approach to renovation, with interventions that are drawn out of an understanding and translation of the existing design, but without merely replicating, nor ignoring. The distinction between existing and new is therefore blurred, with new elements in dialogue with the intentions of the original architects, while establishing a new language. When taken together, the success of these interspersed and relatively minor interventions is in their transformation of a corporate headquarters designed for a single user, into a mixed-use ensemble of spaces that accommodate many different activities and interests. This adaptive reuse reconnects La Royale Belge with the city beyond its moat, by breaking down its defences and opening its gates to a new public.