Published in Blueprint 362 - January 2019

The Louisiana Museum of Modern Art’s latest exhibition presents the work of Chilean architects Elemental, and their rigorous design process takes centre stage.

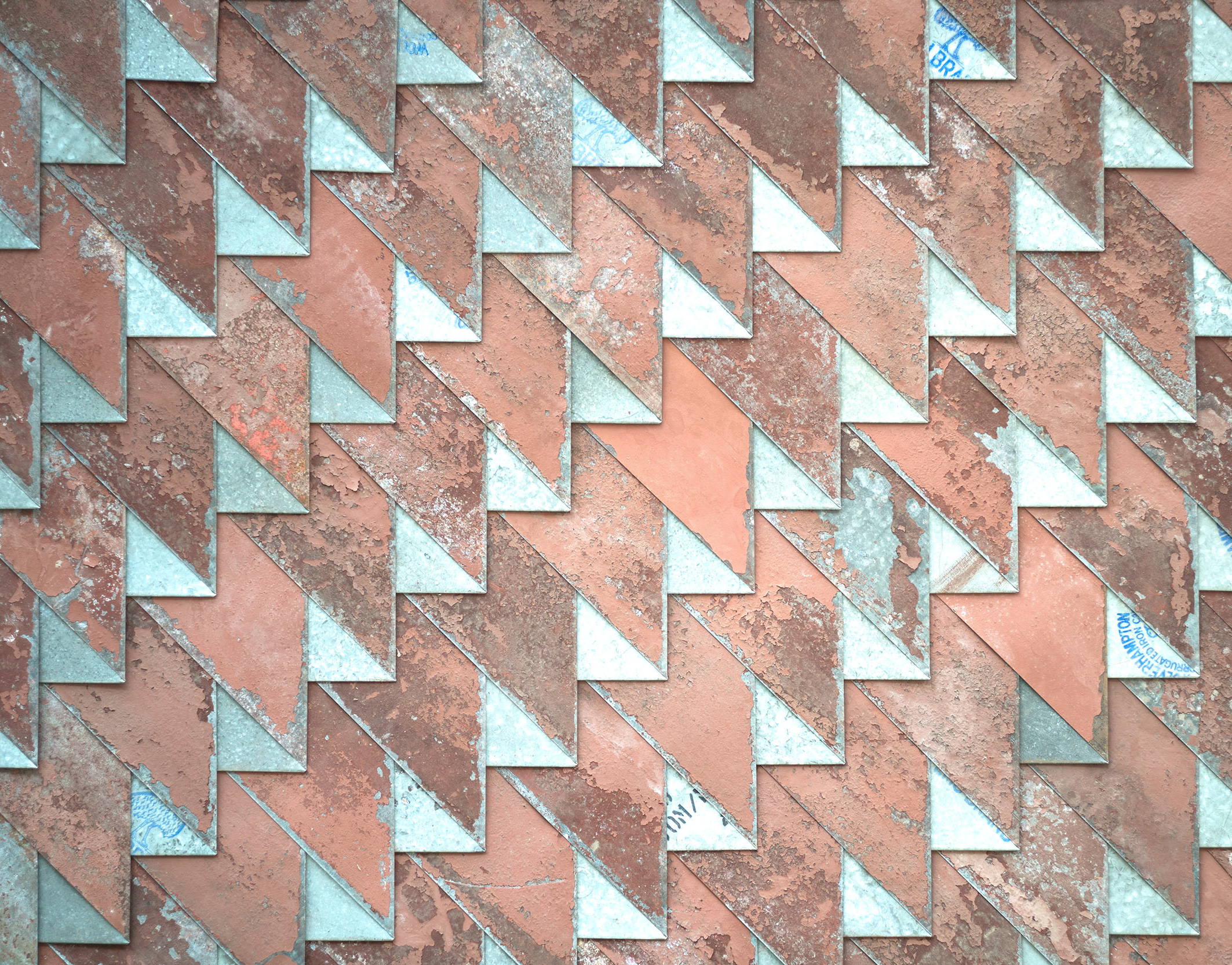

UC Innovation Center, Santiago, Chile, 2015. Photo: © Nina Videc

Alejandro Aravena, the frontman and founder of Chilean architectural office Elemental, has brought his entire staff and their families to Copenhagen for the opening of their new exhibition at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Standing before a vast corrugated cardboard cube that appears to float thanks to an elaborate counterbalance system, Aravena begins by demanding that every visitor lies on the floor to gaze up at silent footage from a drone gliding past a series of their built projects. The cube is intended to manifest the main principles of Elemental’s architecture - the bodily effect of weight, balance and gravity - and this experience is to be intensified through the act of lying down.

There may be a geographical and cultural distance between Chile and Denmark but Aravena suggests that these universal principles can bridge the divide, and it is from this reflection that the exhibition takes its name - ‘So Far …’ . The cube is annotated with an Aravena soundbite scrawled on the wall; ‘at Elemental we give form to the places where people live; it is no more complicated than that, but also no easier than that.’

The truth in this statement is typified by Elemental’s ‘half houses’ - the pragmatic yet radical project that led Aravena to the 2016 Pritzker Prize and the Venice Biennale curatorship with its ingenious approach to social housing in Chile’s slum areas. Tasked with building adequate family housing within tight financial limitations, Elemental realised that they could only afford to build half of the 80m2 required by a typical family. Rather than build substandard housing in the city’s peripheries, Elemental focused their resources into elements that couldn’t be easily changed at a later date - location, structure, circulation and services.

In doing so they built half houses, but within a 80m2 framework that would allow occupants to complete their homes over time. This allowed Elemental to stay within the state’s budget, but also transformed each house into an investment, allowing a scarcity of means to develop over time through incremental appropriation. Elemental used the So Far … exhibition as an opportunity to document the evolution and adaptation of a number of these half houses, which were built in various forms across Chile. Their realisation that a number of these houses had been resold for profit - unheard of within Chilean social housing - is revealing of the subversive power of Elemental’s design approach.

So Far ... ELEMENTAL | Alejandro Aravena. Photo: © Kim Hansen / Louisiana Museum of Modern Art

It is this unique work process, or the ‘internal cooking’ of their architecture, that the exhibition presents and interrogates. The entrance gallery is filled with a shrine to the sketch, adorned with 173 sketchbooks organised across a cantilevering cardboard platform and screens inviting you to scroll through the entirety of the studio’s drawn work, digitally archived especially for the exhibition. These sketchbooks are referred to as Aravena’s ‘originals’ - appropriate for their art museum setting - and are backdropped by montages of diagrams, notes and arrows that join the dots of Elemental’s design methodology. Curator Kjeld Kjelsen reminds us that ‘architects are not only the designers of the form, but also come up with the tools’, and hopes that this study of process will prove insightful for its Scandinavian audience. Even the making of the exhibition does not escape examination, with a wall of snapshots and annotations mapping the one and a half year evolution of So Far…

While cunning that Elemental used the exhibition as an opportunity to document their practice and create a comprehensive archive of their development work, the impact of this wealth of sketches and notes falls flat when there is so little evidence of its results. Beyond a few brief moments of spatial immersion and the occasional thumbnail or sketch model of Elemental’s intriguing architectural output, the exhibition is frustratingly transfixed on process. Aravena insists that ‘it’s about asking the right questions rather than giving the right answer to the wrong question,’ but the exhibition feels so preoccupied with defining questions that it forgets to give any answers.

Elemental’s more recent work is an exercise in abstraction, relying on those timeless principles of gravity and weight for architectural impact, and the exhibition’s fixation on process appears to be compensating for this apparent simplicity, as if to assure us that their work is indeed refined and highly developed. The desire for an introduction to their upcoming work in Moscow, Qatar and across South America is never satisfied, with a modest row of diagrammatic models relegated to a dark corner of the gallery. The exhibition’s message is clear - Elemental’s work is the result of an arduous process of enquiry and iteration - but So Far … leaves you wanting a little more of their fascinating architectural output and a little less of the post-it notes and napkin doodles that precede it.