Tbilisi’s search for democratic urban governance

Tbilisi, the capital city of Georgia, has experienced several distinct epochs of urban governance within its turbulent recent history, each of which has had a marked impact on the city’s urban fabric. The country’s adoption of capitalist democracy after the fall of the Soviet Union promised a new Tbilisi, but a passive civil society coupled with fledgling state institutions left the city exposed to the forces of capitalist urbanisation and its desire for perpetual growth, often at the expense of urban quality and social wellbeing. The city is now in a state of crisis, with severe air pollution, lack of public space and greenery, over densification and endless traffic defining its urban condition.

Tbilisi has moved through eras of ‘citizen urbanism’, ‘developer urbanism’ and ‘politicised urbanism’, and is now reacting to an increasingly active civil society demanding their right to shape the city. City Hall is increasingly responsive to these demands, and an imminent masterplan will set a clear direction for the city for the first time since the fall of the Soviet Union. This creates a determining moment in Tbilisi’s evolution, suggesting it is pertinent to now reflect on the city’s recent urban history and offer a perspective on its future development. Whilst the field of urban actors in Tbilisi is expanding, the current democratic system risks institutionalising the political through consensual governance, thus nullifying its antagonistic potential.

The essay therefore looks towards the creation of a symbolic common space that facilitates a productive agonistic urbanism, allowing a diverse network of urban actors to engage in urban politics through confrontation and negotiated conflict rather than a pretension to common consensus.

An Agonistic Democratic Politics

Georgia’s expeditious adoption of both democracy and capitalism has constructed a complex ideological contradiction; conflict and negotiation on the one hand, and individualism, consensus and the apolitical on the other.

As explored by Rancière, Žižek and Mouffe, the contemporary city has entered a ‘post-political’ condition, where political space is retreating whilst social space is increasingly ‘colonised or sutured by consensual techno-managerial policies.’ This trend towards consensus is built on the acceptance of the capitalist market and the liberal state as the organisational foundations of society, thus negating the need for the political. Mouffe argues that the uncontested hegemony of liberalism prevents us from thinking politically, as political questions are defined as technical questions to be solved by experts and algorithms, not confrontation and negotiation. The dominant tendencies of liberalism are rationalistic and individualistic, which are unable to comprehend the pluralistic nature of society and its inherent contradictions. Liberalism may accept the existence of conflicting views and values, but only when they coalesce into a ‘harmonious ensemble’ through rational consensus, therefore diminishing all antagonism.

Rancière, Žižek and Mouffe all agree that these conditions have led to an almost universal ‘post-political’ era, and its reinstatement is dependent on an understanding of the ‘unconditional primacy of the inherent antagonism as constitutive of the political.’ Mouffe expands on this understanding through her discussion of the hegemonic nature of every social order, which is therefore always challenged by counter hegemonies. She argues that this struggle is central to a vibrant democracy, and is the ‘configuration of power relations around which society is structured.’

However, this ideal contrasts the reality of the post-ideological consensus, where politics is reduced to social administration and every contradiction is excluded through post-democratic governmental techniques. This follows the Foucauldian concept of governmentality as a technique of governance; a regulatory practice which replaces conflict with ‘technocratic approaches that promote unanimity and consensus’. If a vibrant democracy is defined by the balance of two lines of power - of representation and of participation - then the processes of governmentality heavily emphasises the power of representation; the institutionalised process of elected representatives that revokes the requirement for citizen participation, and thus antagonistic conflict.

An Agonistic Urbanism

Considering the crisis of the contemporary city, Mouffe, Swyngedouw and Aureli discuss the potential of agonistic urban politics in resisting the post-political condition outlined above. This agonistic network of governance would allow conflicting hegemonies to confront one another, desiring an end to conflict but also with an acceptance of its perpetual existence, therefore providing an ‘arena where differences can be confronted’ and channelled into productive outcomes. Mouffe argues that this arena is vital in resisting the hegemony of liberalism and its rejection of the political.

Swyngedouw advocates for ‘symbolic spaces for dissensual public encounter and exchange’; a multitude of social spaces, both material and metaphorical, that embody an agonistic model of democratic politics even if they do not yet sit within the context of a larger agonistic political structure. Artistic and architectural intervention only has power in resisting the ‘total social mobilisation of capitalism’ if its field is expanded to engage with a broad spectrum of social spaces and a diversified network of actors, including a more meaningful inclusion of citizens and their right to ‘reshape the processes of urbanisation.’ Particular intervention must be built on an understanding of the political in its ‘antagonistic dimension as well as the contingent nature of any type of social order,’ and therefore requires a close examination of the specific political and social contexts.

The Context of Tbilisi

Tbilisi’s processes of urban governance have traversed several distinct phases in the past three decades, revealing marked shifts of power between urban actors and therefore providing interesting material for an analysis of (realised and potential) agonistic urban politics.

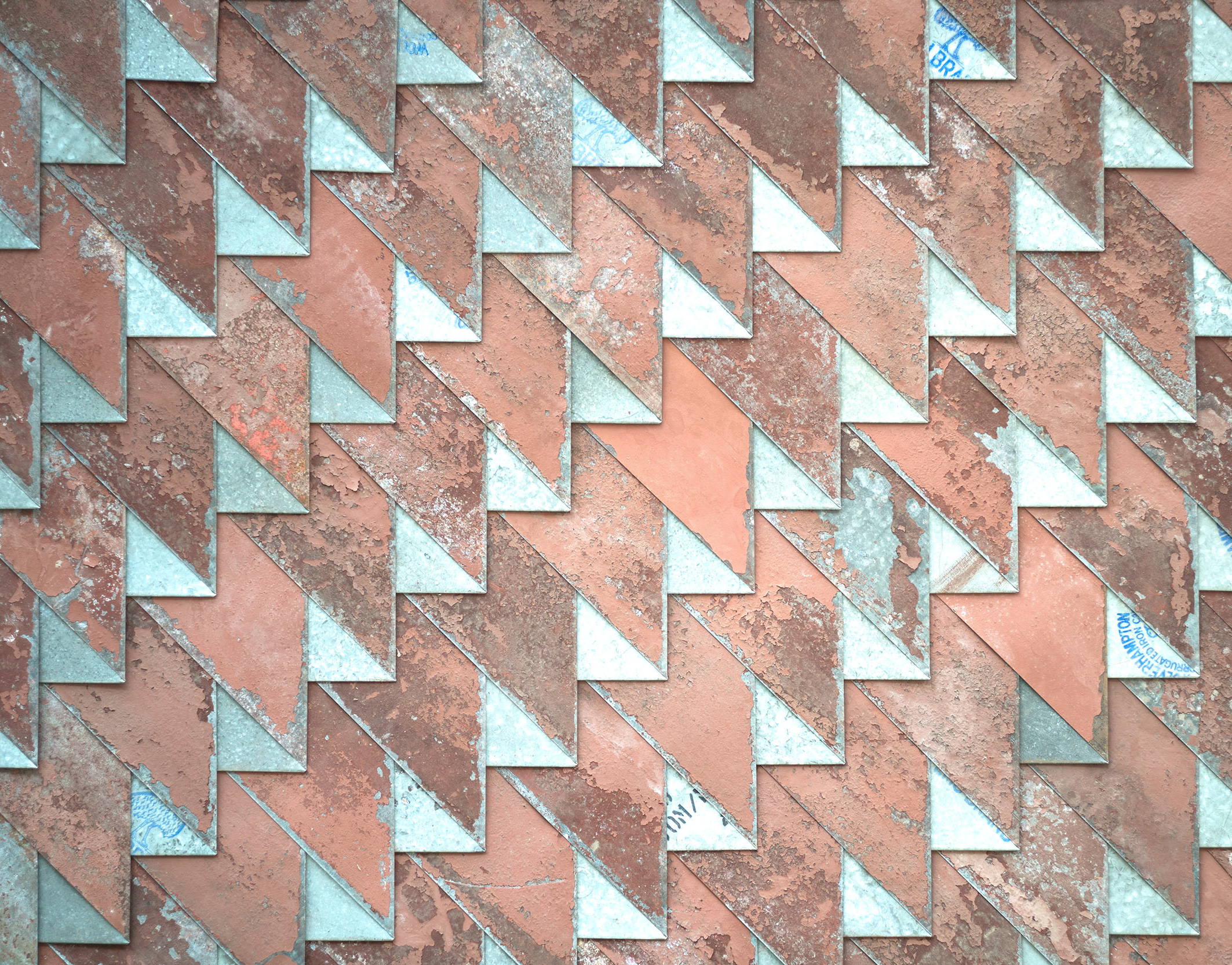

Tbilisi’s current condition is an accumulation of the material effects of these conflicting governance epochs, dense with the ideological ruins of Socialism, parodied democracy and a failing neoliberal order.

Tbilisi Today

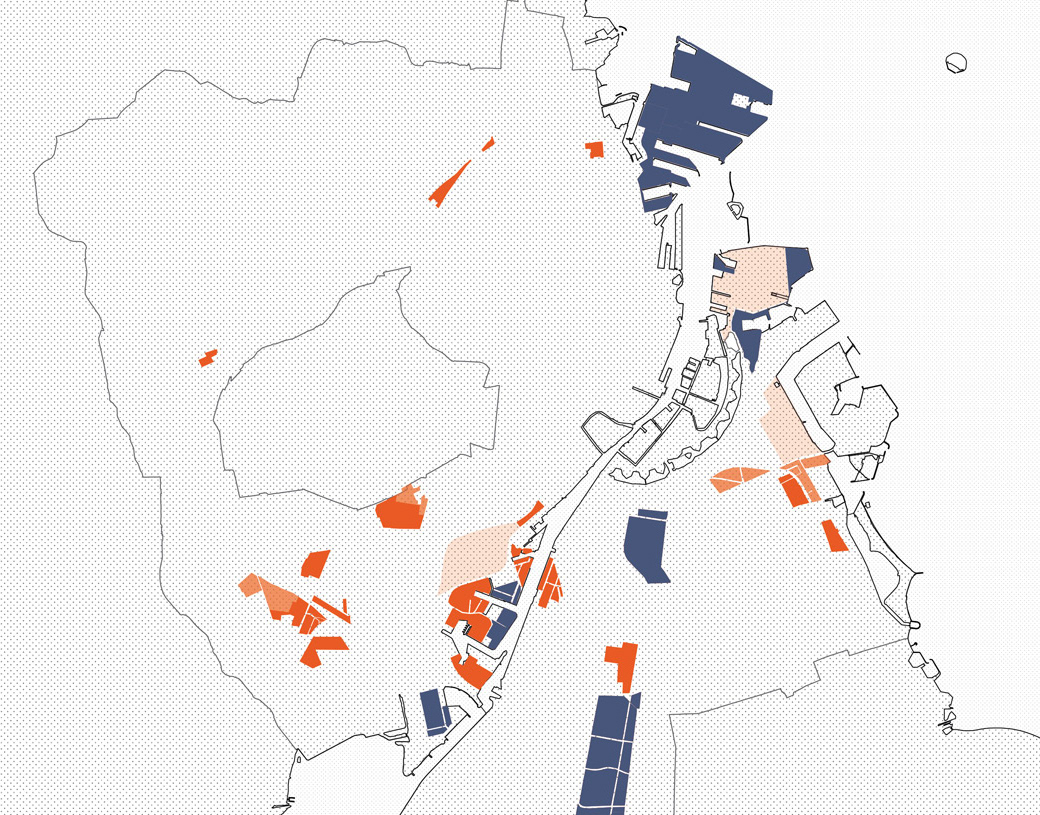

The current condition of urban governance in Tbilisi increasingly represents an amalgamation of the three (post-independence) epochs of urbanism highlighted (citizen urbanism, developer urbanism and politicised urbanism), with the state, developers and some civil society organisations all playing a role in the development of the city. There is an increasingly active City Hall architecture and planning department who have recently begun engaging with citizen groups on specific urban issues as well as regulating developer-led urbanisation. This shift away from a single-actor urbanism represents an expanding actor field, albeit an informal and ambiguous one (see figure 9). Nevertheless, the primary force in Tbilisi’s urban development is still the law of supply and demand, which overwhelms any concept or practice of urban politics through an ‘ongoing radical economisation and depoliticisation of social space’ and the city at large.

The state increasingly resembles Foucauldian governmentality, either organising the urban through techno-managerial or assigning it to the market. A deeply embedded belief that a combination of ‘strong property laws and creative developers will bring out the best possible spatial organisation in the most efficient manner,’ further secures the liberalist hegemony by legitimising its actions, whilst negating the need for centralised planning. The lack of a consistent vision for the city maintains that all urban actors are striving for diverging future cities, and this ambiguity ensures that conflict cannot be productive due to the absence of common grounding.

Citizen participation is widely considered ‘as voting for politicians who will be assisted by civil servants. Scientific experts are useful to define minimum regulation that optimises markets, while minimising social problems… Citizens participate by behaving in a disciplined manner, obeying the laws;’ a system of governmentality that creates an idealised non-conflictual system of governance. There is an increasing number of individuals that resist this suppression, forming activist groups or joining NGOs, but they risk either becoming instituted through ‘public-private stakeholder participatory forms of governance’ or ‘radically marginalised.’ City Hall and other state bodies are increasingly accepting stakeholder antagonism into their organisations, but with an ambition for consensus through managerial processes. Whilst this may suggest improved participation, many of the interviewed actors stated that this had never offered significant results and led to a general feeling of ‘activist fatigue’, in no small part due to the fact that City Hall, however good its intentions, has very limited political or legal power in resisting the liberalist hegemony that prevails.

Furthermore, these activist movements have limited agency as their inherently reactionary form can only respond to concrete socio-spatial issues, preventing a more preemptive or constructive participation. Whilst increased citizen engagement would seem to reflect a more agonistic democracy, Swyngedouw argues that this elevates specific urban conflicts to the political, as ‘rituals of resistance … staged as performative gestures’, thus reducing the sphere of antagonism to a single urban issue (politicising the particular) and maintaining the system that creates them. Mouffe would contend that this activism still plays an important role in the ‘hegemonic struggle by subverting the dominant hegemony and by contributing to the construction of new subjectivities,’ providing that these currently fragmented and isolated citizen resistances are connected across multiples levels of struggle. The lack of this connectivity presents itself as one of main obstructions to the coalescing of multiple urban movements; these fragmented communities have limited power in resisting the tendencies of both governmentality and liberalism.

Salukvadze claims that the current system of urban governance and development is imbalanced with distorted roles, and criticises the ‘lack of consensus and systematic conflict between stakeholders’. Mouffe would argue, however, that striving for this illusion of consensus is to reject the antagonism inherent to democracy, creating a post-political condition that ‘forestalls the articulation of divergent, conflicting and alternative trajectories of future urban possibilities and assemblages,’ even if the existing conflict in Tbilisi’s urban governance is clearly having a negative impact on the city.

This begs the question, how can the conflicting interests of these urban actors be recognised and negotiated into productive outcomes, without acceding to the liberalist trends of an equalising consensus or false politicisation of the particular?

Towards an Agonistic Urbanism?

Whilst democratisation may suggest increased opportunity for wider participation in urban politics, Tbilisi’s recent history has created a complex urban condition with various political, social, economic, and spatial conditions preventing the evolution of an agonistic urban governance.

The history of urban conflict can be traced to its current position in the domain of administrative representational governance, which negates the inherent antagonism of citizen participation and disregards the contradictory nature of heterogenous socio-spatial practices. This post-political condition, as outlined by Mouffe et al., has allowed the hegemony of liberalist ideology to prevail, and its material ramifications now define Tbilisi’s urbanity.

The mapping of these failures has suggested that successful urban governance is reliant on proactive state institutions that define and enforce relevant policy and guidelines, coupled with an active civil society which responds to these impositions, through a critical and formalised network that facilitates participation between the state, the market and citizens. The weighting of power between these entities should be in perpetual flux, but is contingent on this connection to ensure the democratic challenging of hegemonies - the confrontation central to a vibrant democracy and politics proper, as argued by Mouffe et al. As discussed, the potential value in this communication is increasingly recognised in Tbilisi, and the impending masterplan exemplifies this shift in thought. Commissioned through an open competition, a collaboration of governmental bodies and NGOs are working to define an ambitious and holistic direction for the city’s development, for the first time since independence. (see figure 10)

The field of urban actors is indeed expanding, with both governmental bodies and civil society increasingly responding to urban issues, thus suggesting that the dilemma lies not in the lack of antagonism but in the lack of facilitation of this antagonism. Many local actors highlighted the absence of a platform between the state, private sector and civil society through which to facilitate discussion and negotiate conflict regarding urban issues. This is exemplified by the fact that citizens will react strongly to tangible socio-spatial concerns but do not engage with the scale of urban design which creates them, due to the lack of bridging of this scalar void. This essay has made it clear that this absence of connectivity, between both actors and issues, is central to the crisis of contemporary Tbilisi.. The resulting lack of communication presents itself as the main obstacle to a more democratic, agonistic urban governance; there is no space that gives ‘a voice to all those who are silenced within the framework of the existing hegemony.’

The conflict that makes itself heard is in unproductive forms, in isolated incidences, and must be understood as within a system which strives to subdue its contradictions into an idealised and abstracted consensus, reducing its political potential. To move from reactionary to meaningful and transformative participation between urban actors, the voids between them must be bridged, built on an acceptance of the antagonism inherent to their plurality. Whilst this urban politics would be dense with contradiction and conflict, it is essential in its ability to open up space in which a more egalitarian and inclusive city could be imagined and created. Whilst van Assche et al. suggest that the power of representation must be functional in Tbilisi (through a stabilised political system) before citizen participation can be integrated into urban governance processes, Žižek would argue that a true political intervention ‘changes the very framework that determines how things work’; participation between a diverse strata of actors can serve to undermine the existing system of governance and offer alternative possibilities.

The practice of agonistic urbanism in Tbilisi is contingent on two things. Firstly, the provision of spaces for conflictual public encounter and exchange that Swyngedouw and Mouffe advocate, and secondly, the establishment of a bridging, responsive network between urban actors and their particular concerns. The latter is vital in releasing urban conflicts (and actors) from their isolated singularity and connecting them conceptually, and the former is required to allow these antagonisms to confront one another in a symbolic and spatial political arena. A network of this kind would make apparent and visualise the diversity and complexity of conflict in Tbilisi’s urban politics, which must then be facilitated by space (both material and metaphorical) that grounds it in the physicality of the city and allows the negotiation of its contradictions. These spaces are not centralised, but a ‘multiplicity of discursive surfaces’ across a spectrum of scales and platforms which are in constant flux. This arena must allow representation and participation to meet, conflicting agendas to negotiate and antagonism between a diverse network of actors to be manifested, creating a common discourse. To transcend the potential paralysis of hostility, this antagonism must be mediated through frameworks and spaces that aim to reach productive resolutions, moving beyond antagonism to an agonistic urbanism.

Each of Tbilisi’s recent urbanism epochs has failed due to, in part, the dominance of a hegemony that has narrowed the actor field and thus suppressed plurality and antagonism. If Georgia is committed to the democracy project, then it seems an apt moment to consider widening and diversifying this field of actors to allow a polyvocal, conflictual urban politics to emerge. This plethora of formalised and scalar conflicts, connected by a responsive network and hosted by designed dissensual spaces, could constitute a truly democratic, agonistic urbanism.