The Right to Dwell - Manifesto for an Affordable City. Image © The Right to Dwell Think Tank.

“There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them, not buildings, that we must fit our plans.” Jane Jacobs - writer and urban activist

While this may be true when dealing with established cities, how do we plan for districts that are not yet built, and their residents yet to be found? How do we fit our plans to a population that is yet to be defined? Keen to maintain its reputation as a leader in successful urban planning, the city of Copenhagen is grappling with these questions as it builds large new districts to accommodate its growing population and alleviate its chronic housing shortage.

Copenhagen is currently one of the most diverse cities in Europe, accommodating a vibrantly mixed population in terms of income, ethnicity, age and household composition. Renowned for its socially progressive policies, the city has long encouraged this diversity by controlling rents, building state-owned housing, encouraging variety and innovation in ownership and rental models, and investing in a rich and open public realm. A long history of inclusive planning, combined with innovative design thinking, has established Copenhagen as a leading example of how to build housing that reflects the diversity of its population. The municipality’s rhetoric is distinctly pluralistic, emphasizing the social and economic benefits of a diverse city that aims to be indiscriminate in its ‘liveability’.

But in new districts such as the ongoing development of Nordhavn in North Copenhagen, the city is faced with the challenge of engineering this diversity from the ground up. Nordhavn is the biggest urban project in Copenhagen in recent years, aiming to accommodate 40,000 inhabitants in 18,000 homes by transforming an industrial port into a new city district.

CPH By & Havn (City & Port), a private company owned by the Municipality of Copenhagen and the Danish state, have been tasked with this project, following their development of the Ørestad district to the South of the city in the early 2000s. Ørestad is widely considered to be abject failure of urban planning and development, its retail quota consumed by a monolithic supermarket and its housing characterized by a strip of isolated and competing architectural ‘icons’.

One company, By & Havn, own or control the majority of the land in the current and future development areas.

The Right to Dwell - Manifesto for an Affordable City. Image © The Right to Dwell Think Tank.

Field’s, a monumental supermarket that sprawls across a prominent site in the centre of Ørestad, Copenhagen. Photo © Henrik Aslagsen

While in part due to the shortcomings of a masterplan that prioritized a metro line and excessive plot sizes, the failures of Ørestad were also the product of a dramatic shift in procurement strategy - from a state-controlled welfare urbanism to public-private partnerships that leaned towards profitability and laissez-faire development. The resulting district may boast several examples of innovative housing architecture, but they are isolated and lack the connective urban infrastructure needed to accommodate a socially diverse population.

Learning from these mistakes, in Nordhavn the city is attempting to find the balance between a controlled and a market-oriented form of development, in the hope of replicating the social balance found elsewhere in the city while remaining economically viable. An aspirational masterplan by COBE, SLETH, Polyform and Rambøll has attempted to define a vibrant mix of commercial, residential, retail and recreational functions, recommending streets alive with coffee shops and social spaces, and workspaces weaved amongst housing units accommodating a diverse cross-section of society. While these aspirations are important in projecting a vision of diversity through design, it is the strength of legislation that determines the quality of its realization. And in Copenhagen, as in many cities, it is the issue of house-type variation that dominates this debate.

'It is widely accepted that non-profit rental housing helps to ensure diversity.’ Frank Jensen - the mayor of Copenhagen.

In search of this diversity Copenhagen’s mayor Frank Jensen has recently overseen a landmark reform of the Planning Act, enabling the municipality to demand that a quarter of new housing is publicly supported rental housing and therefore open to all (in principle), even in new and expensive districts such as Nordhavn. While a central piece of the diversity puzzle, is this policy alone enough to enable and protect the social balance that the city values so highly?

25% social housing still leaves 75% of housing unaffordable. The Right to Dwell - Manifesto for an Affordable City. Image © The Right to Dwell Think Tank.

The first area of Nordhavn to be completed - the Århusagade district - was initiated before these regulatory mechanisms were approved, and therefore falls shorts of its aspirations, containing just 7% public housing. Without enforced legislation in place, it was the rules of the market that defined the district’s composition, resulting in the likes of the Silo apartment - the most expensive home in Copenhagen. The increasing cost of housing then influences the companies and organizations that choose to move into the area, as they look to reflect their new customer base. With this in mind, it seems increasingly problematic to enforce the inclusion of a single student housing block when the only entertainment is a luxury cinema and the only place to eat a gourmet restaurant. In the words of Politiken architecture critic Karsten Ifversen, the district begins to look less like a diverse neighborhood and more like a ‘prosperous ghetto’, with the benefits of liveability offset by a lack of affordability.

If all citizens spent 40% of their disposable income on housing then only 19% would be able to afford a mortgage for an average flat in Copenhagen.

The Right to Dwell - Manifesto for an Affordable City. Image © The Right to Dwell Think Tank.

While an increased percentage of affordable public housing may shift this balance and encourage a district’s public and commercial realm to reflect a more diverse community, perhaps architects and urban planners can be more proactive in designing diversity from the outset. This requires an increased focus on cultural planning - the composition of public facilities, amenities, creative organizations, retail and entertainment - as an integral part of a holistic urban plan and the infrastructure needed to support housing variation. For architects, it demands new strategies for integrating housing into a public realm that encourages and fosters social diversity.

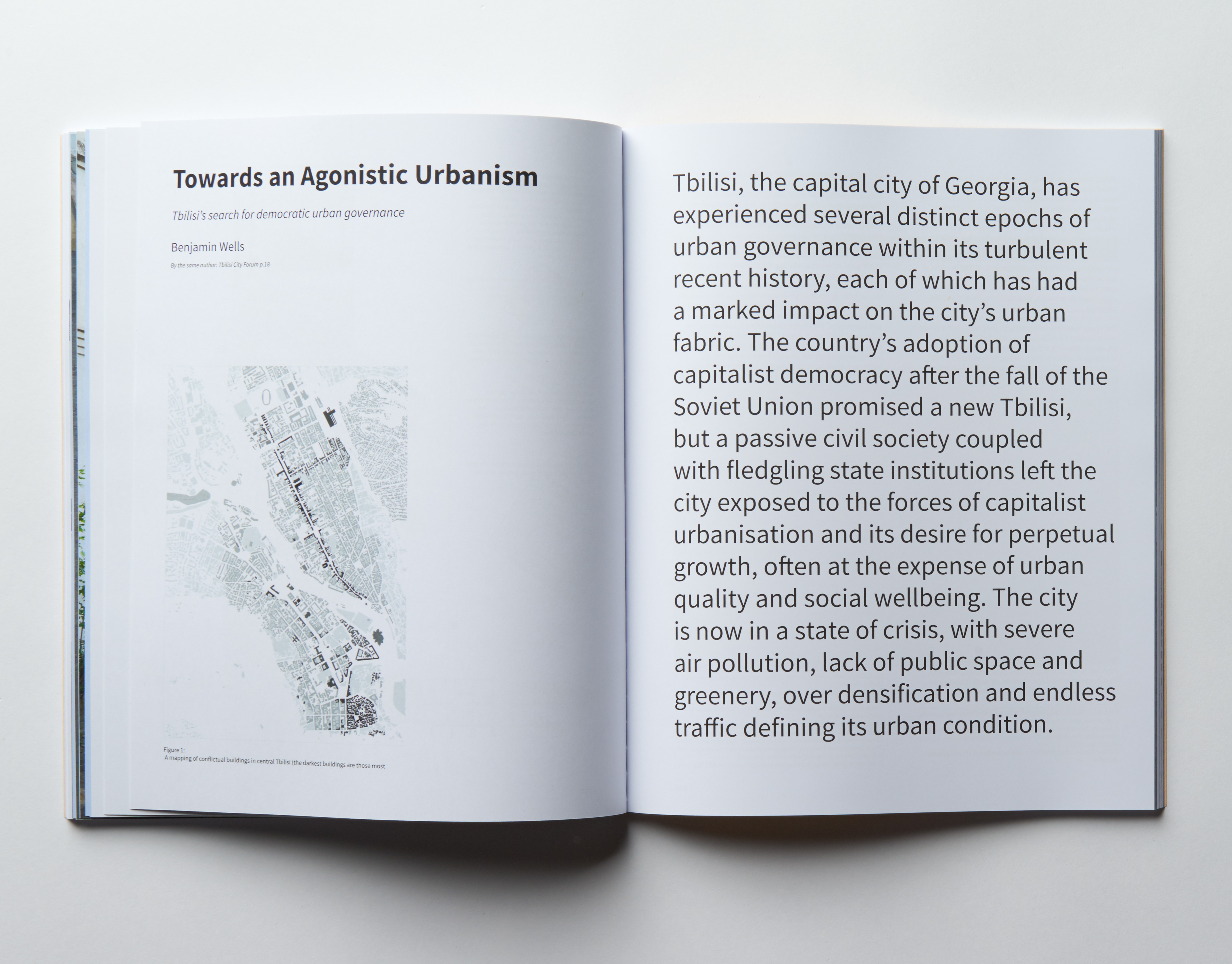

Team entasis have attempted to draw this diversity into their urban plan for Levantkaj, the next portion of Nordhavn’s development (and a part within the area’s overall masterplan). The site is currently occupied by the port’s main shipping container terminal and this geometric organization has inspired their planning approach. In collaboration with GHB Landskabsarkitekter, Niras A/S, Trafikplan and Hall McKnight, entasis have developed a masterplan that challenges the most archetypal of Copenhagen’s urban forms - the courtyard. While Copenhagen’s courtyards have long been appreciated as shared urban spaces, reflecting the diversity accommodated in the surrounding housing, this is dependent on the maintenance of that diversity. As society has become increasingly stratified by rising house prices and wealth inequality, perhaps the courtyard is at risk of becoming less of an extension of the public realm and more of a private and protected enclave.

Team entasis’ urban plan aims to avoid this by omitting the courtyard in favor of more streets, avenues and pathways - connecting 505,000m² of dense and varied new development with a web of accessible and public routes. This streetscape is prioritized over the provision of more formal, representative public spaces, and aims to encourage community and activity through its design, with extensive landscaping and a strong emphasis on ‘green’ mobility.

Levantkaj, as envisioned by Team Entasis. Photo © Ole Malling / Team Entasis

‘The proposal exemplifies a new approach to urban development in Copenhagen, breaking with the urban structure based on courtyard residential blocks found in more recent urban development projects throughout the city.’ Hall McKnight architects, Team Entasis

The urban plan also divides Levantkaj into much smaller plot sizes than those in Ørestad, encouraging a multiplicity of housing typologies and strategies rather than vast, singular housing blocks. This housing diversity hopes to cultivate a societal diversity, and is embedded within an urban strategy that emphasizes community through outdoor recreation and ecological sustainability.

It will take some time before we can discuss the consequences of these design decisions. But Team entasis’ urban plan is compelling in its attempt to embed diversity in the foundations of Levantkaj, by defining the street as an open and accessible public space, and promoting variety in both its architecture and its functions. If in collaboration with a considered cultural planning strategy and a multitude of housing types defined through legislation, perhaps this holistic model would enable the construction of a vibrantly diverse city.

Levantkaj urban plan, by Team Entasis. Drawing © Team Entasis

Further reading:

DIVERCITIES: Dealing with Urban Diversity - The Case of Copenhagen. ‘The project’s central hypothesis is that urban diversity is an asset; it can inspire creativity and innovation and make cities more liveable and harmonious.’ Danish Building Research Institute, Aalborg University.

The Right to Dwell - Manifesto for an Affordable City. ‘This project looks into how planning tools, profit driven architectural (and social) aspiration and real estate polices are building an urban condition of exclusivity.’ The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture. Urbanism & Societal Change.

Architecture Policy Copenhagen 2017-2025 - Architecture for People. ‘It is important to preserve and develop the diversity of Copenhagen through its building and housing stock.’

View at source.