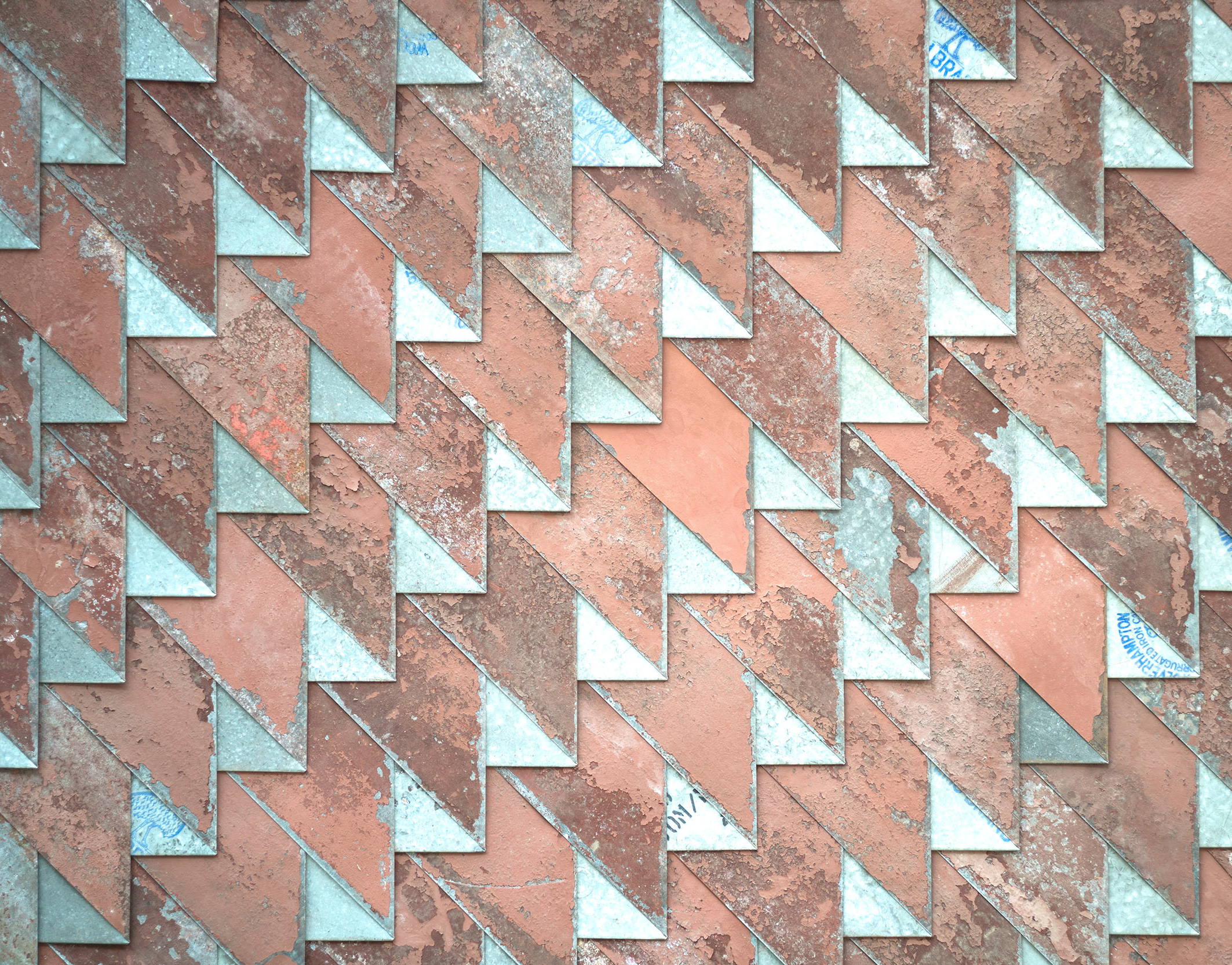

The monumental brick form of Islev church, designed in the 1960s by Inger and Johannes Exner, is a seminal work of Danish modernism. The church is defined by its relentless use of rough red brick that frames church rituals, provides material continuity and creates a strong formal expression.

Inger and Johannes Exner were prolific Danish architects throughout the second half of the 20th century, completing 13 churches, several community centres and many restoration projects such as the Round Tower in central Copenhagen. Islev church in Northwest Copenhagen is one of their most influential projects, varying from much of Nordic modernism in its emphasis on material quality rather than formal vocabulary. The formal expression is striking in its simplicity, allowing uninterrupted brickwork to define much of the church’s textural and architectural character. This, along with a focus on the functional requirements of the assembly and activities of the congregation, contributed to the creation of a new Nordic church typology.

Inger and Johannes Exner were some of the first Danish architects to discard traditional typological frameworks, instead focusing on the rituals taking place within the church. Brick is used to enclose, frame and facilitate the enactment of these rituals, both internally and externally, and there is little symbolic suggestion of the function of the building. Whilst Exner’s churches do present a clear religious interpretation, they prioritise architectural framing and a sensitive contextual awareness that ensured each building is distinct and relevant.

Islev church provides a clear example of this contextual sensitivity, with much of the design responding to a simple environmental concern - traffic noise from the adjacent road Slotsherrensvej. This condition largely defines the form of the church and the resulting brick mass is reminiscent of a defensive fortress - an impression that is accentuated by the absence of apertures and the brick turrets of the corner bell tower.

The boundary wall’s singular expression of its internal character is made when the brickwork curves away from the facade line and is suspended over a low slot at the base of the wall, hinting at the positioning of the altar within.

As the brick form turns away from the road it begins to reduce in scale, creating a series of interlocking volumes that support the main church hall both programmatically and architecturally. This form turns again to enclose the third side of the church’s central courtyard with a low ancillary building, becoming more human in scale and detail whilst maintaining the brick continuity. The courtyard is protected by these fortress-like walls, offering respite from the external context and articulating the processional route from the city to the church’s interior.

The commitment to a single material is carried through to the church’s interiors, where the floors, walls and altar are all crafted from brick, imbuing the project with an aesthetic homogeneity that follows the precedent of architects such as Sigurd Lewerentz. The coarse red brick is constructed with an irregular joint and rough mortar, providing a highly textural surface both internally and externally. A continuous slot around the perimeter of the roof is the only source of daylight within the main church hall, accentuating the texture of the brickwork by illuminating it from above. This detail provides explanation for the curved section of wall seen externally - the increased light intensity highlights the altar as the focal centre of the church. The impressive timber roof structure, based on ancient bridge construction techniques, appears to float between the external walls and offers a lightness to the weight of the brick construction.

Islev Church’s strong formal expression and material consistency was influential in the evolution of a modern Danish church typology which disregarded traditional symbolism in order to emphasis church rituals with architectural qualities. Inger and Johannes Exner’s preoccupation with material and light, coupled with an understanding of contextual factors and the functional requirements of the congregation, led to the design of a building that remains notably contemporary.

This article was originally published on arcspace.com

All photographs © Benjamin Wells 2018.