There are countless neglected housing territories across Europe, in which social spaces are deemed to be negated by digital networks and other realms of interaction. Innovative forms of living are reserved for new housing projects, while existing neighbourhoods are overlooked until the point at which they require significant renovation, or else demolition. This approach forgets the transformative potential of creating social space with Common Forms.

This project establishes an alternative strategy for the architectural amelioration of neglected housing districts.

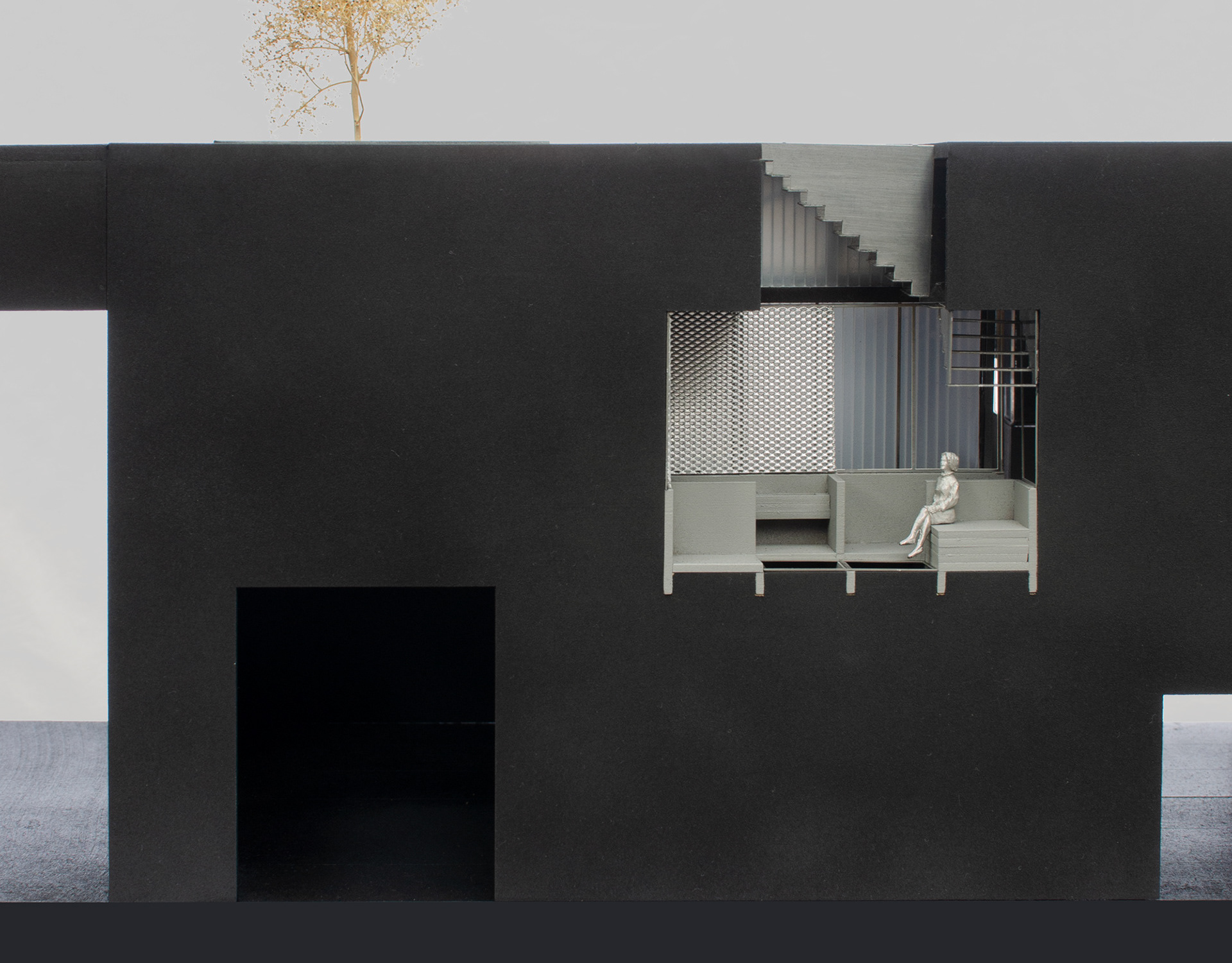

Common Forms occupy the threshold between public and private - their function ambiguous and ownership undefined. Common Forms invite multiple interpretations and uses, encouraging commonality and dialogue in the process. Common Forms are attuned to their specific spatial and socioeconomic contexts, but all share an ambition - to delineate and enable collectivity wherever its potential might have been forgotten.

This line of enquiry is currently investigating Denmark’s controversial ghetto laws, and the ‘One Denmark without parallel societies’ policy that was launched in March this year to address the so-called “black holes on the map of Denmark”.

Danish ghettos are defined as housing areas with at least 1,000 residents that have two or more of the following elements: unemployment above 40%, high crime rates, a lack of further education, low incomes and a majority of non-western immigrants.

These criteria define and delineate 29 ghettos across Denmark, with seven in Copenhagen. These neighbourhoods tend to be on the peripheries of the city, and somewhat ironically they are often associated with architectures designed in the 1970s amid the golden age of the Danish welfare system to provide affordable and equitable housing for the masses.

But by applying a specific GPS coordinate to a complex layering of social problems, these laws conflate issues of race, wealth, unemployment, criminality and education with built form, and in doing so they designate urban areas and their architecture as central to the problem. Places are conflated with people. The political response to social issues of criminality, unemployment or a lack of diversity therefore often becomes an urban one - demolish the ghetto (or perhaps redevelop and sell, if deemed ‘economically viable’).

This conflation creates a state of exception within the city, justifying punitive politics in which not all are equal before the law and delineating a parallel society through an urban limit. The temptation to demolish becomes ever stronger, in a retelling of that enduring myth that the destruction of an urban area equates to the elimination of its social problems.

This temptation is embedded in the proposed ghetto policies, in their demand that no more than 60% of housing in these areas is public. In some cases this defines demolition as the only remaining option. The question of rehousing, or indeed of holistic measures that might alleviate the root of these problems, becomes an afterthought.

In a country famed for its considered and sustainable urban strategies, the desire to demolish is all the more striking.

But if we accept that architecture and design has a role to play in defining these social problems, then perhaps it also holds the potential to alleviate them. The quantity and quality of common infrastructure is central to this, and holds untapped potential in transforming areas deemed to be problematic.

This may include grand interventions like COBE’s recent library and culture house in Tingbjerg, but also demands a forensic analysis of the everyday elements of shared urban environments that might hold potential for averting ghettoisation - lighting, circulation, connectivity, thresholds, common spaces, natural ecologies, technological networks and visual representations, along with an holistic awareness of their wider economic, social and political implications.

Through doing so we might move beyond punitive politics and unjustified stigmatisation to find genuine spatial alternatives to demolition. This strategy may aid the political will to visually homogenise the city, but more fundamentally it holds potential in alleviating the social problems that defined the ghetto in the first place, while avoiding that temptation to demolish Denmark’s elusive black holes.