Ishinomaki, Japan

Pre-emptive Transformation proposes an architectural framework for orchestrating friction between two usually autonomous entities - industry (in this case the fishing industry) and city (in this case the city of Ishinomaki in North Eastern Japan).

This strategy anticipates the inevitable decline of growth-based industries and utilises the process for common good. By pre-emptively hacking an industry’s spatial dependencies, the project circumnavigates the usual procedures of decline, obsoletion, ruin and demolition, instead finding potential in the occupation and transformation of existing resources.

Exhibited at the 2019 Oslo Architecture Triennale, exploring the theme of architectural degrowth.

The project is supported by the Political Architecture MA at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, the Oslo Architecture Triennale and National Museum of Art Norway.

Awarded 2nd place - Social Tectonics competition (Danish and Japanese Architectural Committee).

The project has been exhibited in Copenhagen, Oslo and Tokyo.

Featured in Tribune - Green New World by Merlin Fulcher.

The architectural proposal is introduced not as a solution, but as a framework through which to destabilise both the city’s and industry’s current negative trajectories, by proposing an extreme alternative to their separation. The project offers agency and inclusivity to a multitude of actors and stakeholders who have been displaced from the industry, creating a field condition for their negotiation, with the hypothesis that this could prove to be mutually beneficial for both a stagnating industry and a shrinking city.

It is thus a proposal for transformation - a redefinition of an urban paradigm by consolidating previously isolated events, activities and communities.

AN INDUSTRIAL EDIFICE

The site in question is the port of Ishinomaki, one of Japan’s largest fishing ports. It is here that an abundance of fish are unloaded, sorted, auctioned and then exported across the world. A seemingly infinite multiplication of this process is housed within the recently opened Ishinomaki fish market, which was built to replace the previous market destroyed by the 2011 tsunami. The market was built much bigger than before, spanning almost a kilometre along the coastline and able to process the greatest capacity of any market in the world. This industrial monolith has become a symbol of large scale reconstruction, of Japan’s constant growth and of the industry’s success.

However, it is also a symbol of defiance against the multitude of problems which the industry faces - namely the dangerously low fish stocks due to years of overfishing and a fading workforce where the majority of fisherman are over 60. It has been in decline since the 80s, yet its significance in Japanese culture has ensured its continued support from government subsidies, issued despite its economic inefficiency and environmental damage. It is considered to be one of the most unsustainable industrial practices, and predicted to be obsolete as soon as 2050.

Its intense industrialisation and pursuit of perpetual growth has caused the removal of the communities that once managed this resource sustainably, leading to a kind of depoliticising of the industry. Its processes take place in isolation with a significant lack of friction or critical accountability. These consequences manifest themselves in this building, this edifice. Built to facilitate an unattainable capacity, defined by a 40m truss that encloses industrial processes but excludes civic functions, and symbolic of the bias of reconstruction funds towards large scale industrial projects.

ISHINOMAKI

This industry is set against the context of Ishinomaki - a city which was devastated by the 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami. Whilst the fishing industry has been largely rebuilt, the city is struggling to reconstruct at the same rate. Preexisting trends of depopulation and migration have been intensified, with many moving elsewhere to find housing, infrastructure and community. The city is now characterised by dispersed sprawl, a lack of distinct urban nodes and temporary accommodation. On top of this, the city has been distanced, both geographically and conceptually, from the industry on which it grew. A resident told me that they never used to buy fish - they were always given leftover stock from local fisherman - but now they can only get imported fish from supermarkets; evidence of the complete separation of the city and industry. The result of these problems is that both the city and its industry are shrinking, despite their apparent resistance.

Due to their lack of engagement, the industry has lost its support functions and the communities that once managed it, and the city has been distanced from its economic provision and cultural heart.

The project therefore proposes a coalescing of industry with a multitude of civic functions, and their mutual dependency is exposed spatially. This architectural transformation takes advantage of structural and spatial redundancies in an existing industrial monolith, colonising and densifying it with non-industrial activities, thus setting the stage for productive friction between a myriad of actors.

This proposed architectural framework allows a huge variety of functions to take place within it, but suggests a range from the single dwelling for one of the many displaced fisherman, through market stalls for locals to buy fresh fish, to a series of social organisations and institutes that were once integral to the successful management of the industry but have since been displaced.

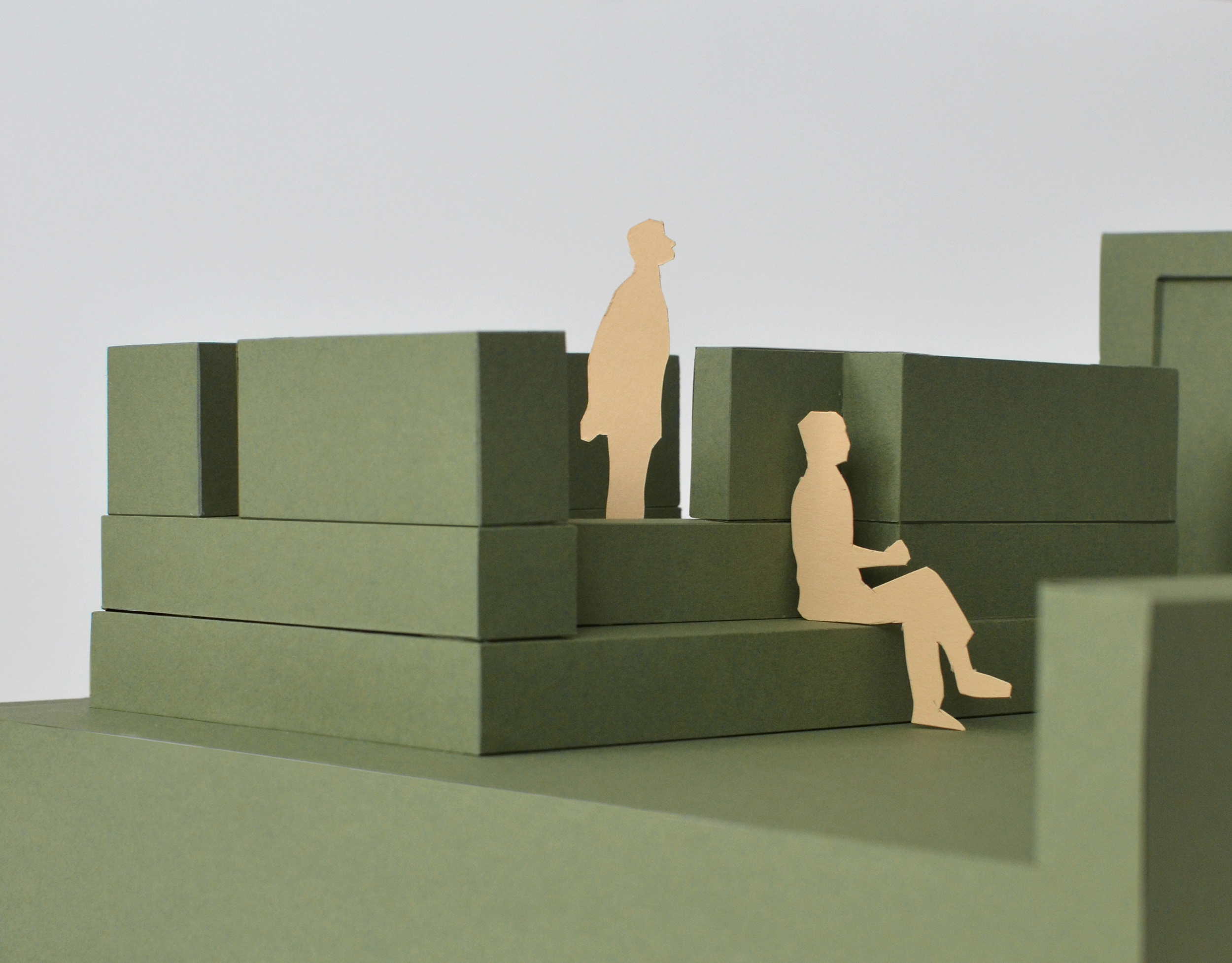

The single cell, multiplied over time to produce a density of urban activity within the structure of the existing fish market.

The accumulation of cells forms a fisherman cooperative - allowing a public to form around a shared concern.

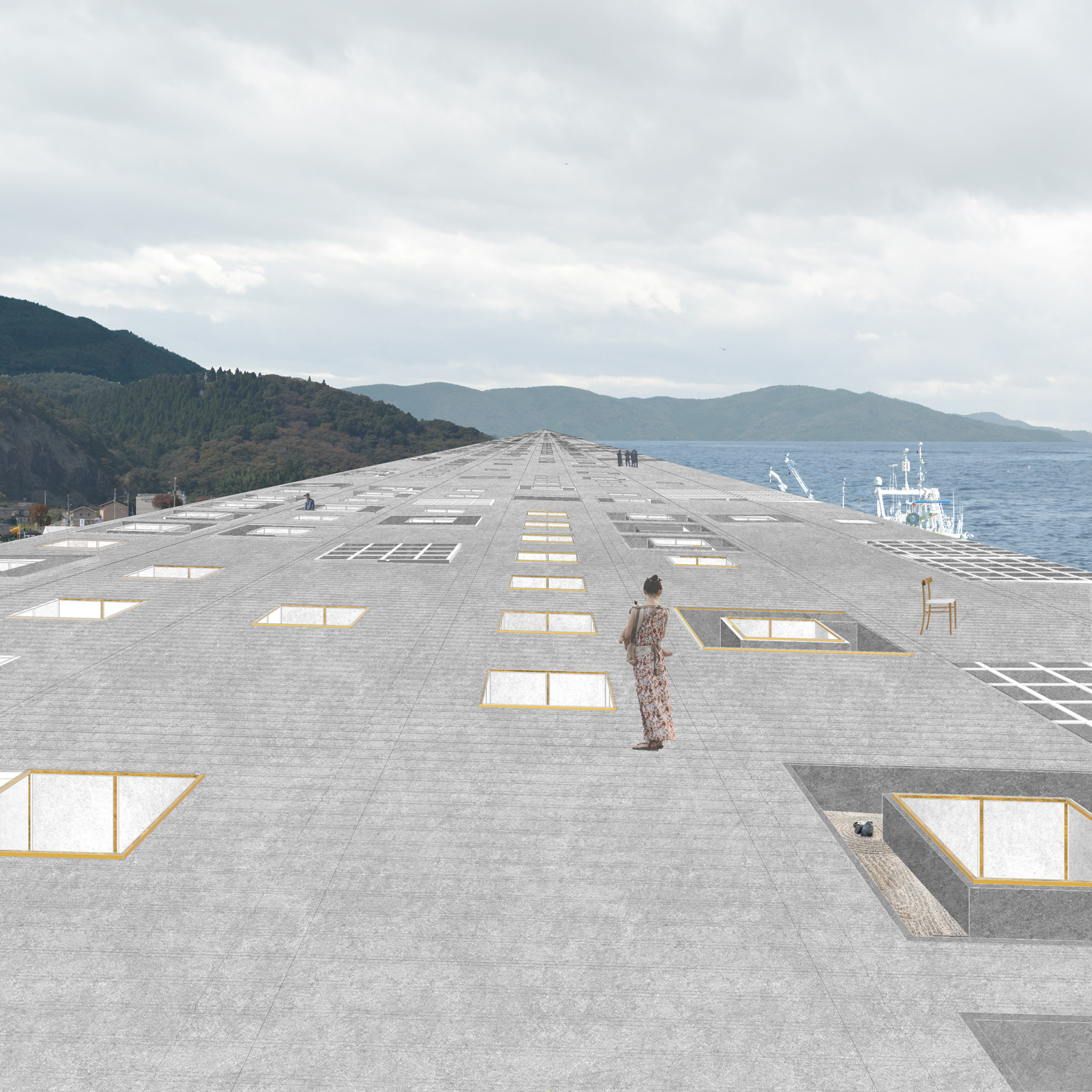

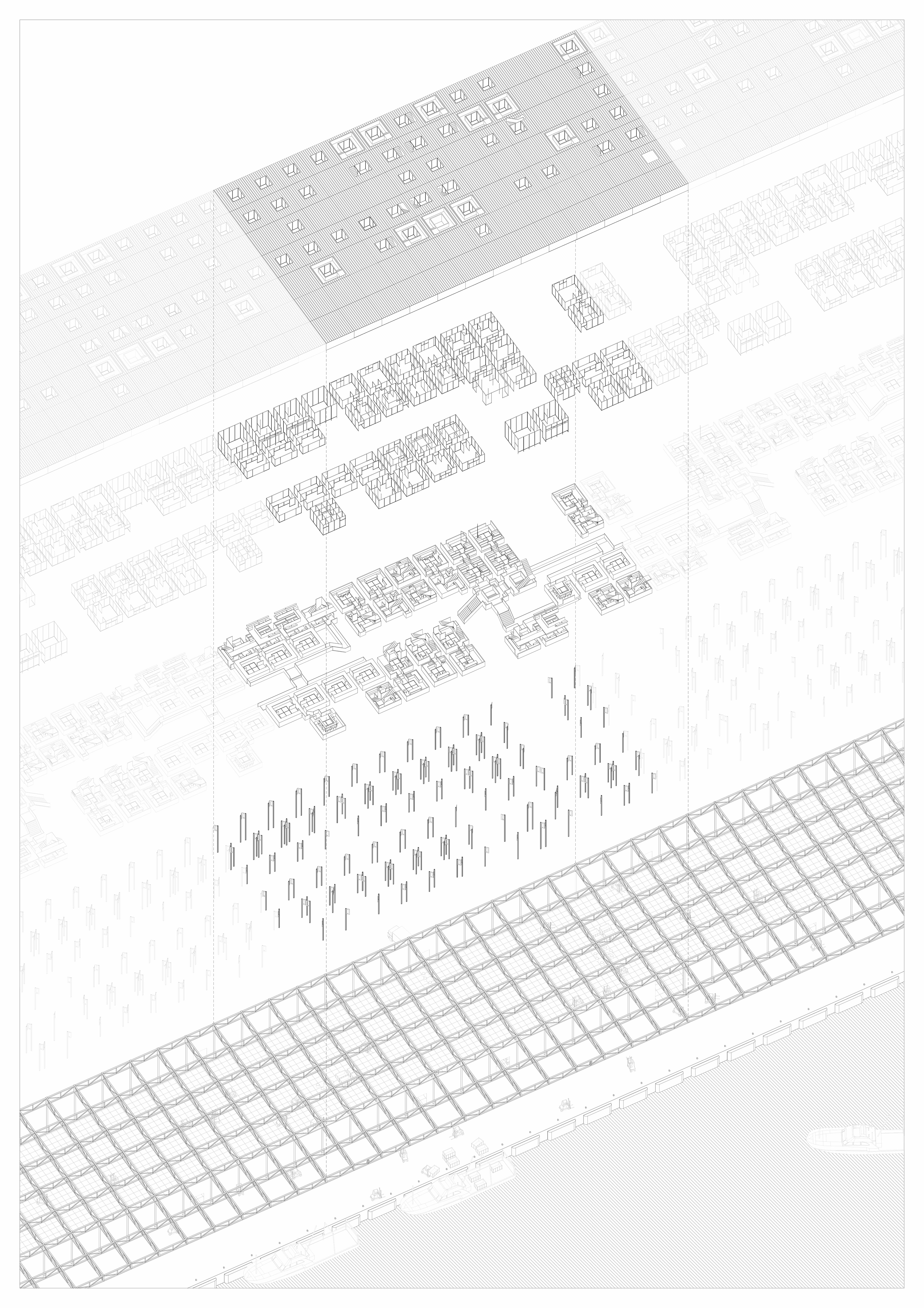

A translucent mesh is hung around the perimeter of the building, marking it as a single monolithic plinth and defining its roof as a new ground datum, the field condition from which the intervening activities descend. Each evening as the fishing fleet returns this screen rises to allow the building to process its catch, thus reacting to the temporality of the industry.

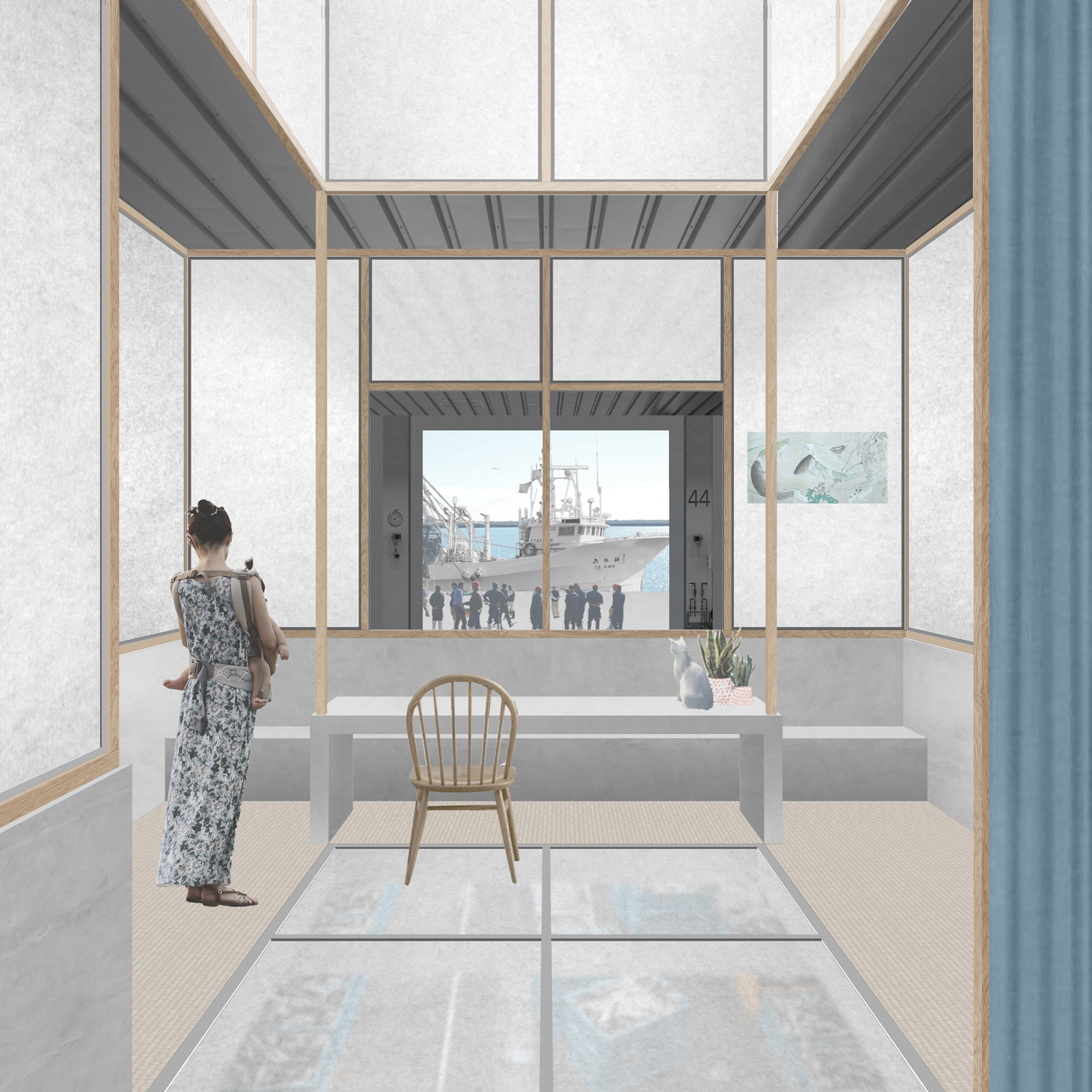

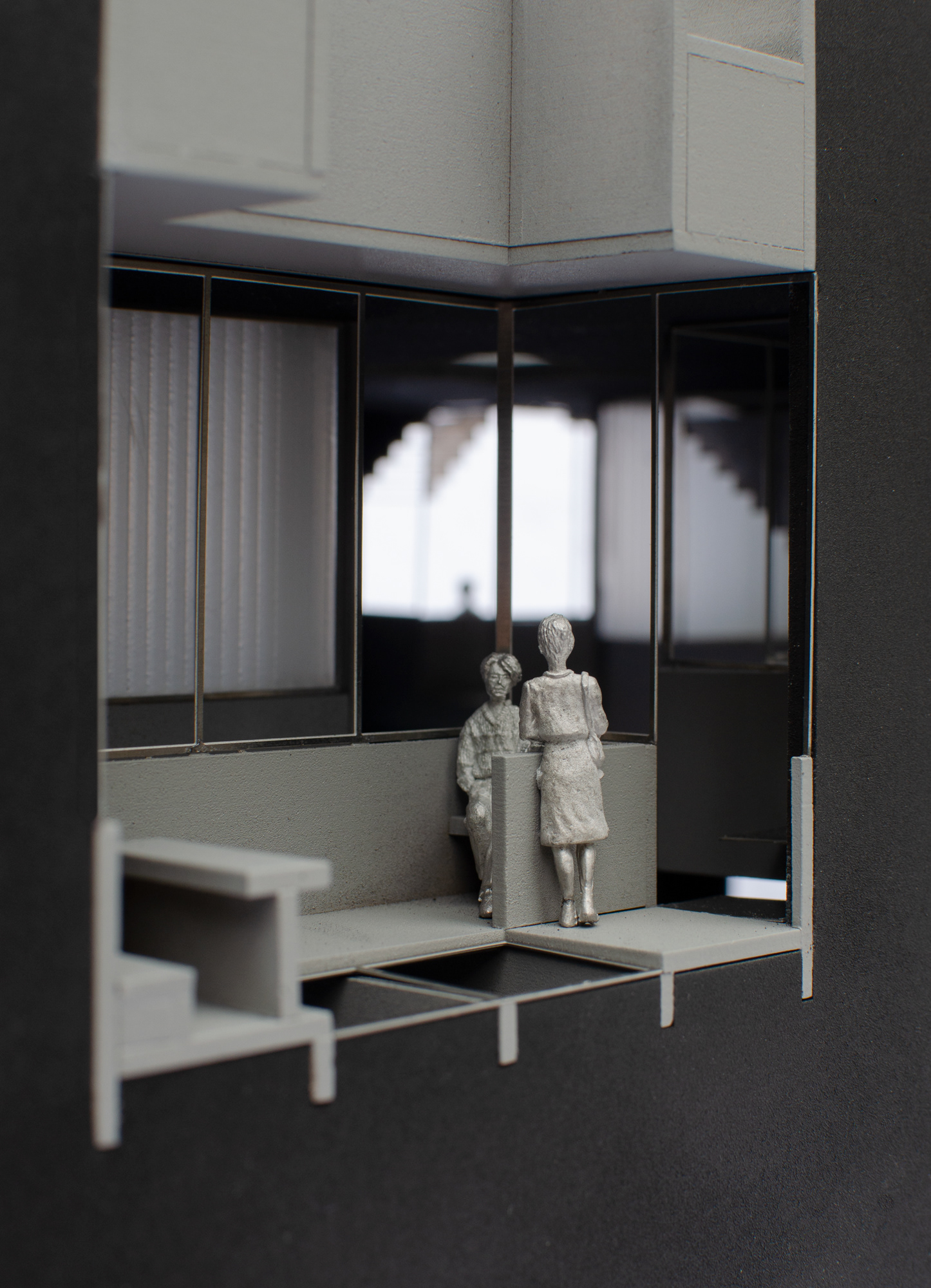

The building’s colonisation then begins with the addition of a single inhabitable cell - its privacy and singularity the antithesis of the global industry. This interrupts the continuity of the roof and places an introverted, individual home within the vast, undefined and multiplied interior of the market. A stair descends through the roof, exposing its structure and its scale, circulating around a central void which offers light to both the dwelling and then on to the industry floor below. Here personalised domesticity is foregrounded against a backdrop of mass industry, light timber framing against steel megastructure.

CONDITION

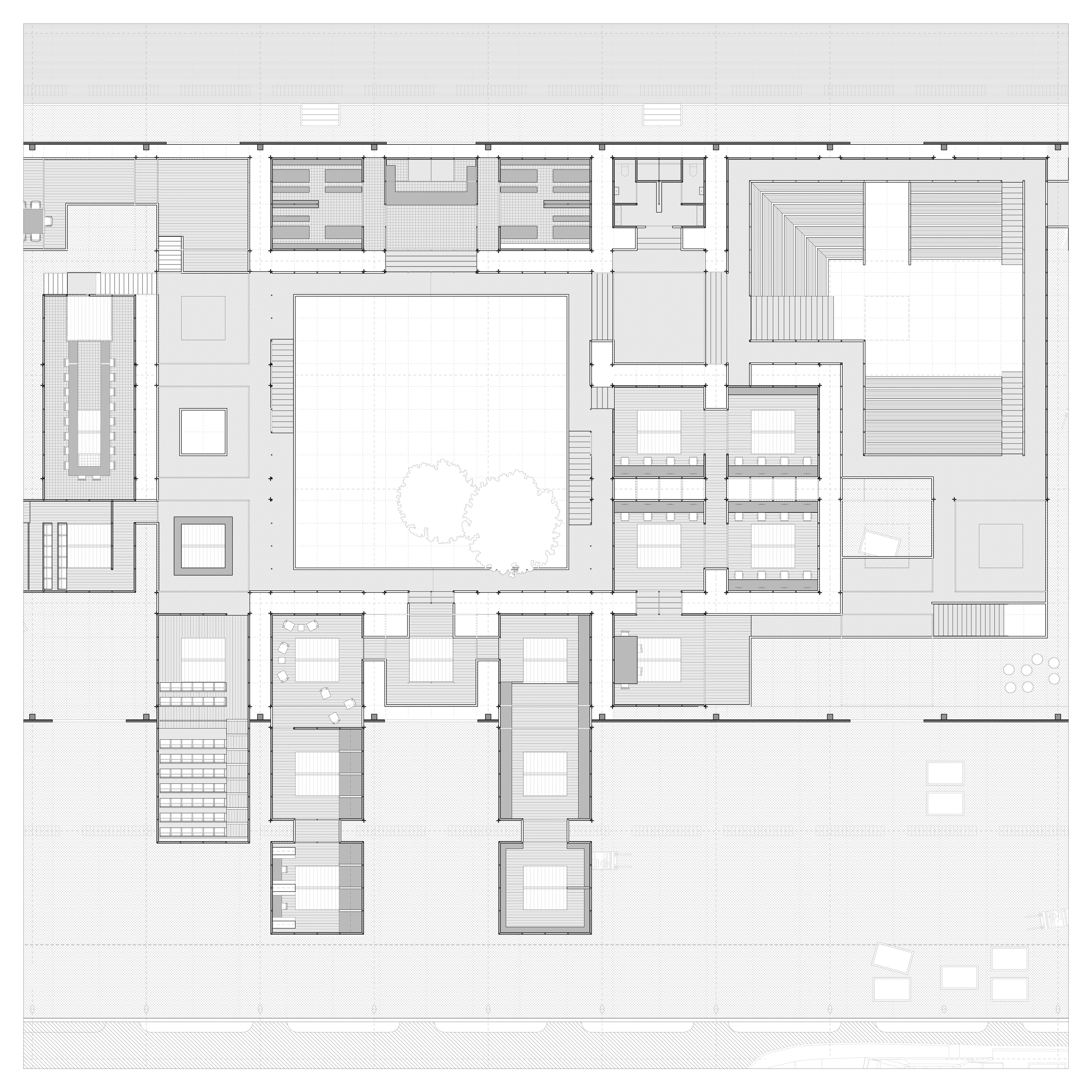

The existing market building provides the condition (the grid, the structure, the circulation and the infrastructure) for the multiplication, the urbanisation of this single cell. Variations of activity and culture then take place within this framework, set against the flow of capital beneath. The intervention is defined by three preexisting elements of the market building - its 6x6m structural grid, its roof truss and its metal cladding, as these provide the possibility conditions for the intervening functions to coexist, and offer them cohesion.

A series of metre deep bases are then introduced, each providing the core functional requirements for one of a variety of programs from dwelling to market stall to sushi bar. These bases provide solidity and variation, at some points allowing the industry to flow uninterrupted beneath and at others descending low enough to impact its procession. These bases are then suspended from the roof to a variety of undefined elevations with tensile steel structures, and enclosed with a light frame holding a series of translucent and timber panels. Whilst the functions of these bases vary, they all have a light void at their centre, therefore acting as a kind of extrusion of the existing roof.

The translucent floor panels can be blocked by the individual users, therefore constantly altering the light levels on the industry base. The temporality of the industry’s processes allows the nonindustrial activities to make use of the base at certain times, and the impact of these will grow and gain permanence over time.

EVOLUTION

The multiplication of these cells may then grow in much the same way as any city urbanises - randomly, chaotically. The continuity and regularity of the roofscape and the undefined processes beneath do not offer an obvious determination of where certain functions should be located - several market stalls may converge, or perhaps a resident will open a restaurant adjacent to his home, with a garden above and the auctioning of tuna below. Some cells may build connections between them, creating suspended streets between shops and sushi bars. With the growth of these cells, the roofscape as field condition, as public realm, is strengthened, gaining spatial hierarchy over both the industrial and civic activities taking place beneath. This zone is indiscriminate of function, acting purely as infrastructure.

Whilst this transformation would be evolving and continuous, it would perhaps reach a point of equilibrium where the industry is restricted to functioning at a sustainable capacity, and the city has reached a level of density optimum for its population.

The architecture of the fisherman cooperative and other organisations are largely defined by the same parameters as the singular cells, but assert themselves more aggressively on the industry. Their ground datum meets the industry’s base, therefore causing a permanent friction and interruption, marking their presence. A central courtyard in each breaks through the roof, exposing the market’s trusses and the sky above, providing circulation and a blurring of the boundary between public roofscape, institutional space and industrial zone below. The negotiations of the organisation are thus introduced into the heart of its object of conflict - the industry.

The introduction of civic programs causes the formerly industrial space to become inclusive and radically open, through the architectural definition and framing of particular activities - the opposite condition of the market as it exists. This monolith provides the structure, the shelter and the cohesion to facilitate the densification of a shrinking city. The market’s redundancy is transformed to offer a new model for reconstruction, therefore diversifying its function before it becomes obsolete. This embraces restricted growth, dynamic scales and negotiation between an abundance of activities, providing a framework for their coexistence.

ALL WORKS © BENJAMIN WELLS 2024.

PLEASE DO NOT REPRODUCE WITHOUT CONSENT.